A Place of Your Own Making: How to Build a One-Room Cabin, Studio, Shack, or Shed: Introduction

| Home | Wiring | Plumbing | Kitchen/Bath |

|

“The purpose of imagination,” wrote Martin Buber, “is to imagine the real.”

Exploring the implications of that tantalizing, multilayered aphorism could easily be the subject of an entire book, if not a life’s work. Yet building a small building—not reading about doing it but actually building the building—can be, in its special way, another means toward accomplishing some of the same thing. I’m not saying you ought to build an outbuilding in order to understand more thoroughly what Martin Buber meant (al though that might not be a half bad idea). But if you do decide to go ahead and build, you may find that, indirectly, Buber will be offering at least as much help as you’ll get from me. I should explain what I mean. Most of us spend a sizable portion of our lives surrounded by wires and windows and heating ducts and pipes, by structural support members fashioned of wood or metal or concrete fastened with nails or rivets or bolts, by sheets of plaster and plastic and plywood and heavy paper soaked in tar, perhaps by tiers of bricks or mosaics of shingles or matrices of boards, and , strangely enough, we call this condition “being at home.” Of course, when we are home, we seldom take the trouble to imagine how all those materials fit together. As long as they leave us alone, we’re usually more than happy to leave them alone. But sometimes one or more of those materials assert themselves. They rot or burst or spring a leak or otherwise malfunction, and suddenly we’re called upon to give them our attention. All along they’ve been quite real, but their reality’s been passive, concealed behind the scrim of God only knows what other competing concerns. Now, abruptly, their reality springs to life and makes us oddly anxious. Probably the anxiety we feel is of two kinds. The first kind has to do with all the questions of how bad the damage is— how much it will cost to fix, how soon it can be got to, how uncomfortable or inconvenienced we’ll be until it’s taken care of; all the obvious considerations that ensue when something crucial doesn’t work. But the second component of the anxiety is much more vague and maybe just as troubling. It’s the component of mystery, of things no longer being in control. What’s gone afoul inside the walls? Just what is it that’s happening in there? You want to allay your anxiety, so, perhaps habitually, you say to yourself, “I’ll call someone.” Whereupon you find a carpenter or plumber or electrician or handyman—someone to whom imagining the reality of walls like yours is all in a day’s work—and, if you’re very lucky, he comes reasonably soon, fixes what ails your house reasonably well, and charges you a reasonable fee. He thereby puts the first kind of anxiety, the kind that comes of things not working right, to rest. But the second kind, the anxiety engendered by the mystery inside the walls, by the fact that there are things nestled in the darkest recesses of your house that you may not be able to fix or understand or even picture, persists. Now you don’t feel quite as much at home when you’re at home. Yes, your house is real enough and really yours, but you’ve had to hire someone else to imagine its reality. When you called in a repairman, what you really did was to take an objective problem, a problem with things (in this case with your house), and transform it into an interpersonal problem. Instead of dealing with what went wrong with your house, you wound up dealing with a person who could fix it. You jollied him into coming promptly, offered him beer or coffee when he got there, negotiated a price that both of you could live with, and maybe sized him up in terms of establishing an ongoing working relationship. But as for your imagining the reality of your house, you ducked the issue al together. Many of those writers and thinkers of the first half of this century who came to be called existentialists, Martin Buber among them, dealt at length with the question of our feeling less at home in the world than perhaps we once did. The world, they said, has become increasingly unfathomable, its reality harder and harder to imagine. In part this was ascribed to the burgeoning complexity of the world, but some of the blame had to be placed with the people who inhabited it. Often we no longer try to imagine the world, to imagine, as Buber put it, the real. Whenever the real needs imagining—and it certainly needs to be imagined by a plumber trying to guess where to chop into your wall to find a leaky pipe—we too often pass the job along to someone else. Now, it’s not my intention here to put repairmen out of business. The world’s assuredly complex, and if we were to refrain altogether from calling upon specialists its complexity would quickly overwhelm us. If I fall off a ladder, crack a rib, and then manage to drag myself over to my doctor’s office, I’m going to be less than happy if his secretary tells me that he’s home tuning up his car. But specialization can also be abused, and habitually resorting to specialists can become a bad habit. Consider the l9SOs stereotype of the father as a man who might be a crackerjack at the office but couldn’t tell child care from a cheese sandwich and was equally clumsy with both. It took a small social revolution to encourage him to imagine the reality of children and sandwiches and eventually the reality of people who deal with children and sandwiches, and his initiation into those realities was probably accompanied by considerable kicking and screaming. But one day, puttering in the kitchen, he realizes that instead of feeling helpless and out of place, he’s actually very much at home. Where he was once an oaf he’s now an adept. He hasn’t renounced all specialization, but he’s no longer quite so addicted to it. His known world has become measurably larger. What I’m suggesting is that far from encumbering your mind with knowledge you’ll never need, exploring the mysteries inside your walls—and doing it by creating a whole new set of walls from scratch—may free you to ponder much greater and more important mysteries later on. I’m suggesting, idiosyncratic as this might sound, that building your own outbuilding is a way back to your home, to the real, to the world.

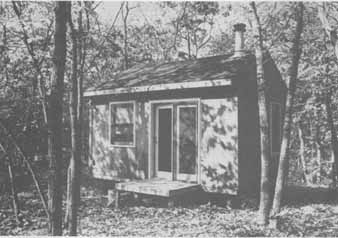

Whether elevated to the rank of “studio” or demoted to the homely designation “shed,” the outbuilding has quietly begun to make a comeback, and the fundamental premise of this guide is that nearly anyone can build one more or less by himself. I don’t mean a flimsy, amateurish junk pile either, although back when they were a commonplace on rural properties, it’s precisely as flimsy, amateurish junk piles that thousands of American outbuildings were born. Until fairly recently, country folk seldom stopped to wonder if they were capable of putting up a small building. They simply went ahead and did it. If the resulting structure was more than a little ramshackle, its improvement was left to future generations. Unless, that's , it fell down before future generations even got to it. Rural New Englanders used to explain why their town hadn’t adopted any formal building code by saying, “What’s the point? If a building ain’t no good, the snows will take it.” Nonetheless, the outbuilding we’ll be describing here is a sturdy, weathertight structure that’s eminently usable, decently presentable, and capable of passing muster with just about any building inspector. Given some guidance and a modicum of hand-holding (both of which, first time around, are likely to be at least as important as “how-to” instruction), an unskilled layman can expect to put up such a building in a surprisingly short time and for surprisingly little money. And when he’s done, he’ll have the bargain hunter’s private delight in getting what he got for considerably less money than he’d have paid a specialist (read “builder”) to do the job. The value of his property will have increased far out of proportion to what the outbuilding actually cost, and he’ll also have had the chance to be outdoors regularly and for a good reason. He’ll even have had some occupational therapy of the best sort, in that he really wanted the end result. He’ll have the pride of accomplishment that ensues from building something substantial, useful, attractive, and enduring. For a time he’ll have had—and the importance of this isn’t to be minimized—a fresh obsession to replace the ensemble of old obsessions that normally beleaguer him. And he’ll wind up with the pungently subversive pleasure that comes of successfully practicing a craft without taking a whole lot of time or effort to master it.

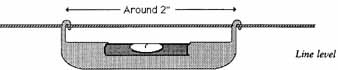

Which brings up the question: if you’re going to build a building and you don’t have much craftsmanship to draw on, what do you have to draw on? Well, it’s here that I’d like to touch on the concept of field expedience. If this were a conventional how-to guide, it would bear more than a passing likeness to a recipe book. Before beginning to tell you “how-to,” it would rigorously list the tools and materials you’d need to do the job. Yet the stance that proper tools are essential to a task is one the novice can choose to adopt or leave alone. A craftsman who keeps making the same things again and again, who’s deeply wedded to long-held routines, would understandably be lost without what he feels are the proper tools. The beginner needn’t be that hidebound. Not being a craftsman, he’s not obliged to behave like one. But, lacking craftsmanship, the novice builder is by no means without resources. He can still put his trust in ordinary competence, ordinary good sense, and ordinary ingenuity. If craftsmanship develops over time, competence, good sense, and ingenuity can be tapped right now. When a board has to be sawn to a given length, you can do it with an everyday hand crosscut saw, a hand backsaw, an electric circular saw, a table saw, a band saw, a radial-arm saw, a power miter saw (some times called a chop saw), a hacksaw, a saber saw, or the little sawblade in a Swiss Army knife. (If you’re unfamiliar with tools — especially power tools — take a look at a Sears catalog just to see what’s around.) Used correctly, any one of those will get the job done. It’s true that some will get it done faster than others, or more easily than others, or with more probable precision than others. But they’re all capable of doing it, and even apart from cost, it may take considerably less time to cut a board with the “wrong” saw that’s close at hand than with the proper saw that you have to make a round-trip to the hardware store to buy. So, in the name of field expedience, you really don’t have to assume that any tools other than a decent claw hammer, an ordinary level, a line level, a tape measure, a standard 7-¼ inch circular saw with an all-purpose blade in it, and maybe a nail-puller and an inexpensive caulking gun are essential to this project. I’ll mention other tools as we go along, but the chances are excellent that whatever household tools you have around will suffice to pick up the slack. A hefty stone can accomplish many of the same things that a framing hammer can, and one day when you can’t remember where you’ve left your hammer you may, in a fit of field expedience, find yourself reaching for a stone. Craftsmanship can sometimes be an impediment to ingenuity. Field expedience encourages it.

Where the experienced carpenter does have a clear edge over the novice, however, is in the crucial area of terminology. A seasoned builder can walk into a lumberyard or a hardware store and reel off a shopping list that, to a beginner, might easily sound like so many ravings in medieval Ruritanian patois. And it’s here that a guide can be very useful to the tyro. Watching the guys on line ahead of you be treated with deference and respect simply because they appear to know what they’re talking about only to be patronized nearly to the point of pity when your own turn at the counter comes is an experience there’s every reason to avoid. When you build the outbuilding, there’ll be enough dues to pay without having to be hazed in the bargain. Still, it’s not on public occasions but during those building sessions when the only discourse is between you and the lumber that the real power of terminology becomes most apparent. Having names for things is one way a carpenter puts himself at ease with them. It’s not hard to imagine such a carpenter staring warily at a narrow strip of sheet metal in a lumberyard and slowly working up to asking the clerk, “What’s that?” If the clerk expects to keep his job, one reply he won’t make is “Are you kidding me? You don’t know what that's ?” Knowing what things are is at the heart of any seasoned builder’s self-esteem, and the clerk would be far more likely to say something like “Aahh, it’s just some new kinda drip edge supposed to stand up better to cedar fascia that’s got a lotta sap in it.” The builder would know exactly what the clerk means, and so, if you build the outbuilding, will you. Because the builder’s own internal glossary of terminology has let him easily capture some new bit of knowledge, he feels more comfortable now, and so, as your own construction glossary grows larger, will you. For the first several sessions you may not be very fluent at assigning names to all the tools and materials you’re using, much less to the processes you’re carrying out or the intermediate results you achieve. But then, as you begin using your tools and materials and this guide more and more, as you begin using yourself more and more, your repertoire of terminology will grow. And the more fluently you can name things, the more secure you’ll be in your possession of them. After all, if you own a house, what you have is just a house. But if the house has soffits, and you know what soffits are (maybe because you’ve worked on some), you also own soffits which, in a sense, you wouldn’t otherwise own. The message is simple. By acquiring some new terminology in the course of building the outbuilding, you wind up “having” more things without physically increasing your inventory of possessions. The “having” is interior. It’s in you. And that’s another reason to go ahead and build. Yes, when you’re all done you’ll have a small building that will serve whatever private purpose you have in mind. But a building’s just a building. The real increase in your assets will be in your imagination. A word as simple as “roof” may come to mean something much different than it did before. It may conjure images of rafters, plywood decking, ridge and soffit vents, overlapping layers of roofing felt, nailheads carefully left unexposed—of disparate materials joined by a variety of techniques to compose a functioning entity. Suddenly this mundane monosyllable—’ ‘roof”—will resonate in your imagination as it never did before. And we’ve already noted that the purpose of imagination is exactly that: to imagine the real. Of course, now that you see the direction we’re taking, you may not want to have as ordinary a word as “roof” explode so disconcertingly every time you hear it. You may prefer not to know what’s inside a roof, or, for that matter what’s inside anything else. You may feel that having “roof” reverberate that way will bombard you with more mental clutter than you care to contend with. The inner truth of roofs—of anything—may be repugnant to you. You may be perfectly pleased with an imagination that hovers near the surfaces of things and leaves their innards for others. You may, in a word, be shallow and even want to stay that way. There are circles—shallow ones, to be sure—that endow certain kinds of high-toned shallowness with an aura of chic, and you may aspire to be a member of such a circle, if you aren’t one already. Unfortunately, there’s nothing terribly chic about building an outbuilding, and if you routinely see construction details as mere clutter and would just as soon not change, this may be a good time to stop reading and pass the guide along to someone else. If, on the other hand, you’re intrigued by the sort of change I’m speaking of, building the outbuilding may be a step toward bringing it about. You set forth with a simple enough wish: to have an outbuilding or studio or shed or cabin or detached cottage or one-room shack or whatever you w2cnt to call it and maybe to save some money and get some exercise in the bargain. But as the structure starts going up, the nature of your quest evolves. The building proceeds to change the builder. As your manual skills develop, your confidence swells. Materials which, only a few days ago, were a little awesome and intractable are now familiar and obedient. There’s a growing harmony between you and your tools. On a given day they seem able to do more things than they could the day before. Nails start going in faster and straighter and with fewer blows of the hammer. Building any building—even a little one—is no small task, but gradually you begin to feel it’s a task you’re more than up to. And by the time you’re done—you’ve been to the lumberyard and the hard ware store many times by now, and at both places you’ve long since given up your self-deprecating stammer—there comes a moment, however brief, when you’re certain you could build the Taj Mahal, or at least its rustic equivalent in wood. You’ve hit a new plateau, and you can’t keep from patting yourself on the back.

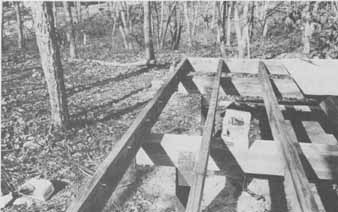

I mentioned the dues you might have to pay to come as far as that, but they’re hardly exorbitant. People who talk about changing in some sought-for way will insist on their “no pain, no gain” caveats, yet there’s something in the very nature of the process of putting up a building that makes the evolution of your skills comparatively painless. Step by step, your proficiency grows as it’s most needed. At the outset of the project, the foundation asks for very little in the way of expertise, so your ability to transfer what’s in your imagination to the ground or to the wood doesn’t have to be especially refined. You’ll get an early feeling for your tools and materials, and the foundation will forgive all but the grossest mistakes. Then, when you go on to the deck, you’ll need only slightly more precision than you needed for the foundation, and when you finish it you may find yourself aching to use your developing facility on something more demanding. And sure enough, framing the walls, the next step in sequence, is just that thing. By the time you’re in the homestretch you’ll be trimming the inside of the building— making windowsills, baseboards, all the woodwork that draws the closest and most frequent scrutiny. And by then, having practiced at cruder tasks, you’ll have gained enough proficiency to make the work look decently professional and maybe even ornamental. Newfound skills have a way of asking to be practiced ornamentally. Finally I’d like to take note of the fact that whenever this guide makes reference to the imagined reader, the clerk at the lumberyard, the counterperson at the hardware store, or any number of other characters apt to be encountered en route, they’re all called “he.” While women oughtn’t in any way be intimidated by the prospect of building an outbuilding, it would be foolish to pretend that the great majority of this guide’s users won’t be men. Still, say what you like about the sexual revolution of the past several decades, it’s certainly made it practical for a woman to undertake the building of an outbuilding with out being thought of, or feeling like, a freak. An oddity, maybe, but not a freak. The nail does know who’s swinging the hammer, but what it knows is whether the swinger is hitting it squarely or obliquely, not the composition of the swinger’s hormones. I’ll continue to say “he” for my own convenience, but I doubt that any woman seriously inclined to build a small building will let herself be flustered by a pronoun. My assumption throughout much of the guide is that the reader will be building alone. However, where it’s unsafe or impractical to work alone, I’ll suggest that help be found. And if good help becomes available at other times, even when safety isn’t a factor, it would be unwise not to grab it. Materials can be very heavy, for men as well as women, and help that’s truly help is always welcome. I hope this guide will be of help. Also see: Do-it-Yourself Log Home / Cabin |

| HOME | Prev: Index | Next: |