Carefully chosen designs for garden projects will go for naught if inappropriate building materials are used. A material may be inappropriate for esthetic reasons—perhaps too rough in size or texture where delicacy is more its order, or so garish in color that it commands undue attention. But a material is more likely to be inappropriate because it won’t survive the gar den environment: sun, wind, rain, freezing, thawing. Some materials are naturally weather-resistant; others can be made so with special treatment. Characteristics to consider as you select materials are discussed here.

Adobe

A building-block material made of clay soil and water, with straw sometimes added to give strength, is called adobe. An asphalt stabilizer is commonly added to retard weathering, but this greatly increases the cost. Structures of any size can be built with these molded, sun-dried blocks, one of the oldest construction materials known. Adobe bricks are used in terrace floors.

Common in the U.S. only in the Southwest where soil of the right com position is found, adobe bricks and blocks are so heavy (12 to 45 pounds each) that the cost of transporting them to other regions is prohibitive. Further more, adobe without stabilizing asphalt can be used only in an arid or semiarid climate; frequent hard rain would melt it away. But it lasts indefinitely if it stays dry, as Indian relics attest.

Adobe bricks and blocks are sold regionally at manufacturing plants, where you also can buy clay soil by the cubic yard for use in mortaring and plastering. The blocks commonly are 4 by 16 inches across their faces and from 3½ to 12 inches deep; the bricks are 6 by 12 or 12 by 12 inches and are usually 2½ inches thick.

Walls built of adobe are laid in courses like other brickwork and re quire strong foundations and, if higher than 2 feet, steel reinforcement as required by the local building code. Paving bricks are set on a bed of sand. Since dimensions can vary from block to block and brick to brick, tight-fitting patterns are not appropriate.

AGGREGATE See Concrete, Sand, Stone

Aluminum

Aluminum building materials are such relative newcomers that many people still object to having them in a garden. But there is no denying aluminum’s many advantages over more traditional materials. Aluminum is lightweight, extremely strong for its weight, easily worked and almost maintenance-free. Readily cut with ordinary tin snips, a hack saw or a power saw with a metal- cutting blade, aluminum products are easy to shape and install, though gloves and goggles are advisable if power tools are used. Over a long period of years, aluminum is more economical than most other building materials.

Among the products available for garden projects are aluminum lath, in sect screening, threaded rods, louvered sun screening and panels that are flat, corrugated, crimped or perforated for use in fences, overhead structures and storage buildings. Many products are finished with baked-on paint that resists chipping, peeling or blistering. Also available are fencing panels and posts that mimic familiar patterns: the gothic picket, board-and-board, basket-weave and other designs.

Asbestos board

Of all materials available for outdoor construction, asbestos board is one of the most durable. The flat or corrugated sheets made of cement and asbestos fiber are used for fences, windbreaks and overhead structures where a long, maintenance-free life is important. Asbestos board is impervious to fire, corrosion, weathering and pest attacks. It may be primed and painted, but if left its natural cement-gray color it needs no maintenance at all. The durability and low maintenance are offset by its relatively high cost and brittleness.

The sheets come in standard widths of 42 or 48 inches and lengths of 4, 8, 10 and 12 feet. Panels /8 to ½ inch thick are recommended for outdoor use. The sheets can be cut, using a tungsten-carbide saw blade; they can also be snapped like pieces of glass after being scored on both sides. Drill all fastening holes before beginning installation. Weighing 2 to 4 pounds per square foot, depending on the thickness, asbestos board is a heavy material that requires strong supporting posts.

Since the asbestos fibers are locked into the boards by cement, asbestos board presents no health hazard until it’s cut. If you cut or drill it, work in an area that has good ventilation and wear a face mask with a filter to avoid inhaling any loose fibers.

Asphalt

Asphalt is a tarlike substance that becomes a durable paving material when mixed with gravel and sand. Properly installed asphalt surfaces are almost as durable as those made of concrete or bricks and considerably less expensive than either. Unlike concrete, asphalt is easily patched if the soil beneath it sags or heaves, causing cracks. But poorly mixed and compacted asphalt can be come a nightmare of sticky shoes and crumbling edges. Because the dark color absorbs heat, an asphalt terrace can be uncomfortably warm unless it’s well shaded. Still, asphalt paving is an economical choice for such large areas as tennis courts, driveways, service yards or long garden paths.

TYPES. The most durable kind of asphalt is hot-mixed asphaltic concrete. A combination of hot asphalt and gravel that is factory-mixed and delivered by truck, it’s applied as a liquid that hardens as it cools. Proper installation re quires professional skill and equipment.

Cold-mix asphalt is a mixture of aggregates and asphalt suspended in a liquid. After the mix is spread and compacted, it hardens slowly as the liquid evaporates. Designated by grades as slow, medium or fast according to its hardening speed, cold-mix asphalt is available at building-supply and hard ware stores in 60- to 100-pound bags for patching or surfacing small areas. It may take months to harden completely.

Emulsified liquid asphalt is poured over a gravel base. Available in bulk and relatively easy to use, it hardens so quickly its best use is in small areas.

INSTALLATION. For asphalt paving, first excavate, grade and compact a soil bed where the paving will go. Treat the soil with a weed killer to keep plants from growing through the asphalt later. Build wooden forms to establish the shape, drainage and thickness of the asphalt—generally 1½ to 2 inches for a driveway, 1 to 1½ inches for walks and terraces. Plan to leave the forms in place permanently to prevent crumbling edges. In regions where the soil freezes, compact a 3- to 4-inch subbase of sand or other fine aggregate. Then spread on the asphalt mix and roll it firmly. The wet surface can be finished by brushing sand or pea gravel over it and rolling it in. Hardened asphalt can be colored with special plastic paints.

BEAMS See Wood

BLOCK See Adobe, Concrete, Glass, Stone

BOLTS See Fasteners

Brick

Some 5,000 years ago, man discovered that a hard, durable material could be made by baking clay in a mold. The bricks that resulted have been a popular building material ever since. Bricks have become available in more than 10,000 combinations of color, shape, size and texture. Despite such variety, most can be classified as common, face or paving bricks.

COMMON. The most economical for garden use are common bricks, also called building or sewer bricks. Usually red, they measure 7½ to 8 inches long, 2¼ inches thick and 3¾ to 3½ inches wide. Three kinds of common bricks that are frequently used in garden construction are wire-cut, sand-mold and clinker. Wire-cut bricks are straight- sided, rough-textured and often pitted. Smoother sand-mold bricks are turned out in molds so the top face is slightly larger than the bottom. Clinker bricks, also called hard-burned, are the toughest; they are often overbaked, causing black patches and surface irregularities, so clinker bricks are used where they won’t show.

FACE. More expensive for garden- construction projects, face bricks are sometimes used to make decorative walls, walks and planters.

Most face bricks are made with holes in them to make them lighter, if these are used for paving, they will last longer if they are set on edge.

---

CHOOSING BRICK FACING

After you have decided on a size and grade of brick for a garden wall or paving, you have a choice of many different surface textures. For walls, esthetics are generally the only considerations, and any of the six types of facings shown below will do. Paving requires additional attributes: it must be both safe and comfortable to walk on; because of their uneven surfaces, stippled, rug and water-struck bricks are rarely used underfoot.

COMMON BUILDING BRICK; SMOOTH BRICK; SAND-FINISHED BRICK; STIPPLED BRICK; WATER-STRUCK BRICK

---

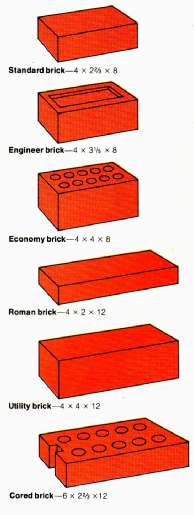

SIZING UP BRICKS

Bricks are available in a wide variety of sizes and shapes, from elegant, narrow Roman bricks to oversized utility bricks. Cored bricks are not weaker, as might be supposed, but are lighter and easier to handle. The dimensions of the modular bricks listed below are nominal, including allowance for a mortar joint.

Standard – 4x 2 2/3 x 6

Engineer brick—4 x 3 1/5 x 8

Economy brick—4x4x8

Roman brick—4x2x12

Utility brick—4x2x12

Cored brick—6 x 2¾ x 12

---

PAVING. Solid paving bricks are particularly durable underfoot in the gar den. They are available in such colors as brown, yellow and pink as well as red. Paving bricks are slightly larger than common bricks. Special paving bricks only 11/4 inches thick are some times available and are set in place with mortar like tiles. Paving bricks have a rough texture for good traction and to reduce glare.

Paving and face bricks are available with various textures on the side that will be exposed to view, including rug, which is striped with deep grooves; sand-finished, with grit embedded; stippled, with a rough, mottled look; and water-struck, with an etched, sculptural appearance.

OTHER BRICKS. Used bricks, re claimed from old buildings and cleaned of mortar, have a worn and weathered appearance difficult to duplicate artificially. Such reclaimed bricks can be used in walls or for paving but they should be set on concrete bases.

Fire bricks are made to withstand very high temperatures. They are used in the garden to line barbecue pits.

BUYING BRICKS. All bricks are graded according to their weather resistance.

Bricks rated NW don’t have weather-resistant qualities and are for interior use only. Bricks rated MW (moderate weathering) can be used outdoors where only a few days of freezing temperatures occur. Bricks rated SW (severe weathering) can be used in contact with the ground in very cold regions.

When you order bricks, add 5 per cent to your calculated needs to allow for breakage and replacement. Five standard bricks set tightly without mortar will cover 1 square foot, as will four and one half bricks set with a ½-inch mortar joint. Bricks are commonly sold in 500- and 1,000-brick cubes. Buying bricks in such standard lots is economical and ensures that they will be roughly the same color and size, although bricks within the same lot can vary in size as much as 3 percent.

BUILDING ANCHORS See Fasteners

Canvas:

Tightly woven cotton or acrylic canvas, available in a number of weaves, finishes and weights, may last up to 10 years outdoors. The types commonly used include heavy-duty army duck and lightweight drill. Vat-dyed canvas is the least expensive but is not as colorfast as vinyl-laminated or acrylic- coated canvas. Vinyl-laminated canvas is also more resistant to soiling. Most manufacturers treat canvas with fire- resistant and mildew-proof chemicals; both are highly desirable.

Canvas weighing from 6 to 18 ounces a linear yard is sold at awning stores in 31-, 36- or 54-inch-wide rolls. Ten ounce canvas is suitable for awnings and overheads, 8-ounce is used for porch umbrellas and 6- to 8-ounce fabric is made into furniture covers.

When you work with new canvas, al low for a shrinkage of 3 inches in each linear yard. Sew with extra-strength polyester thread, since cotton may rot. Ten-ounce canvas is the heaviest that a home sewing machine can handle.

Mildew is the worst enemy of can vas. Be sure that awnings and umbrellas are completely dry after rain before they are folded. Before canvas coverings are taken in for the winter, they should be hosed with cold water, scrubbed with a soft brush and dried while they are on the frames. Store canvas in a cool, dry, well-ventilated area protected from rodents.

= = = =

METHODS OF CURING FRESH CONCRETE

Fresh concrete must be cured by being kept moist for several days. Water starts a chemical reaction that bonds the ingredients of the concrete, so that the longer you cure it the stronger it will be—a week is generally sufficient. The table below evaluates techniques for curing fresh concrete.

>>Technique:

WAYS TO ADD WATER:

1. Covering with a pool of water

2. Sprinkling by hand or hose

3. Covering with burlap or matting

4. Covering with straw, sand or earth

WAYS TO KEEP WATER IN:

1 Applying chemical curing compounds

2. Covering with plastic film

3. Covering with waterproof paper

--Advantages:

- Insulates and gives optimum results

- Inexpensive and works well if done regularly

- Works well if kept constantly wet

- Inexpensive and insulates from cold

- Works well and permits lengthy curing

- Watertight and easy to handle

- Works well if tightly overlapped at edges

--Disadvantages:

- Usable only on flat surfaces

- May dry between sprinklings; walls drain too quickly

- May dry out

- May dry out; difficult to remove; earth may leave stain

- Usually requires sprayer; rain may wash off; weak insulator

- Must be weighted down; may cause discoloring

- Usable only on horizontal surfaces; expensive and hard to handle

= = = = =

Carpeting (outdoor):

Most indoor-outdoor carpeting is suit able only for use on porches, terraces and decks that have roofs to provide partial shelter from the elements. How ever, “turf” carpeting made of polypropylene olefin fibers—the type used to cover football fields—is durable enough to withstand any kind of weather.

Turf carpeting has a rubber or vinyl backing. Available in 6- and 12-foot widths, it comes in a wide range of colors and patterns as well as the familiar green. Several grades are sold by the square yard by carpet retailers. It can be rolled out loose or installed with adhesives on any well-drained, hard surface. It needs only an occasional sweeping and hosing to keep it clean.

Cement:

Portland cement is a bonding agent that is combined in various proportions with lime, water and aggregates such as sand and gravel to make concrete, mortar and stucco.

“ Portland” is not a brand name but a type of cement produced according to strict standards. Its English inventor, Joseph Aspdin, named his mixture for its supposed resemblance, when cast, to the fine limestone quarried on the English Isle of Portland. The cement is a free-flowing powder made of minerals obtained in large part from limestone.

Building-material dealers sell port land cement in moistureproof paper bags weighing 94 pounds and measuring 1 cubic foot. Don’t buy broken bags; moisture absorbed from the air will ruin the cement.

Epoxy and latex cements are used to patch old stucco or concrete. Epoxy mixed with sand and cement makes an extremely strong patching compound, but like all epoxy products, the elements must be combined just before the compound is needed and any left over mixture must be discarded. Latex cement can make a repair that is all but undetectable. It’s sold in 5-, 10- or 40- pound bags of dry cement and latex to which water is added or as separate cans of liquid latex and powder.

CHAIN LINK See Wire fencing CINDER BLOCKS See Concrete

= = = =

FROZEN WATER: THE UNDERGROUND ENEMY

[Line and number = FROST-LINE DEPTH IN INCHES]

Water in the soil nourishes all plants in mild weather, but when the water freezes, it can cause serious damage to fence posts, wall footings and paving blocks.

Freezing water expands, moving the surrounding soil. When the ice thaws, the soil is subjected to further disturbance. To prevent this damage, footings and posts should rest on stable soil beneath the frost line—that is, the deepest level of frost penetration. Bricks and other payers can float on top of a base of sand or poured concrete if you use grades of brick that are matched to the frost conditions in your area.

As shown on the accompanying frost-line map prepared by the U.S. Weather Bureau, the depth of the frost line varies in this country from an inch in northern Florida to 72 inches in northern Maine.

Altitude, weather patterns and composition of soil also affect frost-line depth. Thus, in relatively flat States, frost depths are fairly uniform, but in the upper Midwestern and western states, the patterns vary greatly be cause of mountain ranges or soil diversity.

Local building codes generally are a good indication of the depth of •the frost line, al though in some areas the codes may require deeper footings, than the depth of the frost alone would necessitate.

= = = =

Concrete:

A mixture of Portland cement, water and an aggregate such as sand, gravel, crushed rock, vermiculite or cinders, concrete is used in garden projects in liquid form that can be shaped and smoothed before it hardens or as pre-cast concrete blocks used like bricks.

POURED CONCRETE. Dry ready-mix formulations for making concrete, pack aged in the proper proportions, are handy for small projects. You simply add water and mix, usually with a hoe in a metal wheelbarrow. For somewhat larger projects, it’s more economical to buy the ingredients separately, either mixing them by hand or in a rented portable power mixer. For very large projects, such as a terrace or a drive way, you can buy transit-mixed concrete, poured from the truck that mixes it and delivers it to the site. Such dealers usually will deliver only a cubic yard or more. Transit-mix concrete must be poured and smoothed rapidly; prepare excavations and forms in advance, and have helpers on hand with the necessary rakes, shovels, floats and trowels to level the mix.

===

BLOCKS FOR EVERY PURPOSE

Several kinds of cinder blocks and concrete blocks are available for gardening projects. The stretcher block is the most common type; its hollow cores and end projections assure strong mortar joints. A corner block is identical to the stretcher except that one end is flat so it can be left exposed. A half block is used to start a running-bond pattern of staggered vertical joints. Partition and half-height blocks are used to provide weep holes in retaining walls for drainage. Coreless blocks and solid-top blocks are used where cores would be unsightly, as in the caps of walls and planters. Screen blocks, of which three representative types are illustrated, are used to build airy, decorative walls and partitions.

CORELES BLOCK; PARTITION BLOCK; HALF-HEIGHT BLOCK; HALF BLOCK; SOLID-TOP BLOCK

===

CONCRETE BLOCKS. There are more than 1,000 choices of patterns and textures in concrete blocks. As building blocks, they are inexpensive and are good insulators against cold and noise. Most have hollow cores but are still heavy; handle them carefully to avoid muscle strain. Concrete blocks are virtually maintenance-free.

The most common sizes of concrete blocks are 8 by 8 by 16 inches, weighing 40 to 50 pounds, and 4 by 8 by 16 inches, weighing 25 to 30 pounds. In both cases, the actual dimensions are inch less than the nominal dimensions, which allows space for a mortar joint.

Concrete blocks are formulated to suit particular climate conditions. Type II is suitable for most areas, but Type I is recommended for very dry climates where Type II blocks might shrink and crack. A lightweight 8-by-8-by- 16-inch concrete block, made with vermiculite or cinder aggregate instead of gravel, weighs about 25 pounds.

Split blocks are long and thin with rough faces. Slump blocks, which sag slightly when removed from their mold, resemble stone. Glazed blocks resemble tile. A range of colored blocks is avail able in some areas, although all blocks that are not glazed are easily painted.

Various patterns of grillwork and screen blocks can be laid on edge in a wall to provide ventilation and a decorative pattern. Special surface textures, too, are available for decorative use.

Concrete block walls 4 feet high or more are laid on a foundation of concrete poured over vertical steel reinforcement rods that give extra strength. The thin, solid concrete blocks used to cap a wall can also be used as paving blocks, set on a bed of sand and held in place with header boards.

Fasteners:

NAILS. Formed from wire or cut from metal plates, nails are the quickest and simplest fasteners to use for joining wood. Aluminum or stainless steel nails are preferable for outdoor use since even galvanized nails may rust.

Nail lengths are usually designated in “pennies,” abbreviated “d.” Most kinds of nails range from 2d (about 1 inch) to 60d (about 6 inches). Those commonly used in garden construction are shown in the table opposite. Use nails two and a half to three times longer than the width of the board you are nailing for the strongest joint.

SCREWS. With their threaded shanks, screws make stronger joints than nails and are especially useful if the lumber is not thick enough to hold a nail securely. Decorative screwheads are preferable where fasteners are exposed.

Screws are classified by both length and gauge; the higher the gauge, the thicker the screw. The heads of the screws may be flat, round or oval, and may have either conventional straight screwdriver slots or the cross-shaped Phillips-head slots. All are available in a great variety of rust-resistant and decorative finishes. Choose a screw whose length is two thirds the total thickness of the boards being joined. Screws with fine threads are best for hardwoods; those with coarse threads bind softwoods more tightly.

=====

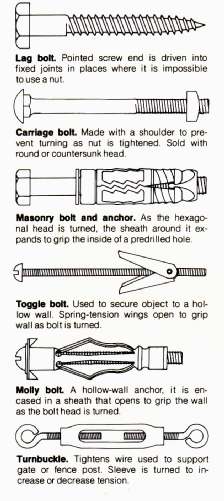

FASTENERS FOR EVERY NEED

The fasteners that are commonly used for garden construction and general carpentry are illustrated here. Some, like nails, can be used for a variety of jobs, while other fasteners, such as toggle bolts and post caps, are intended for specific purposes.

NAILS

Available in a range of lengths for an endless variety of jobs, the nails shown are measured by inches and by penny ratings. As a general rule, a nail should be three times as long as the thickness of the wood being secured.

Common nail. Made with a broad head, it won’t pull through a board.

Siding nail. Used to fasten exterior siding; head can be countersunk.

Finishing nail. Used for fine work; head is sunk, then covered with wood filler.

Masonry nail. Forged from tempered steel, it’s used to join wood t masonry.

Annular-ring nail. Ridges lock into wood, giving great strength.

WOOD SCREWS

Used where joints will be subject to stress, screws hold more firmly than nails. They are sold by diameter, length, type of metal and type of head.

Oval-head screw. Tapered shoulder can be partially counter sunk for holding power.

Phillips-head screw. Double slot reduces slippage. Heads may be flat, oval or round.

Round-head screw. Head won’t penetrate wood. Often used in temporary structures.

Flat-head screw. Preferred where screw will be invisible; head is fully countersunk.

Framing anchor. Used to connect a corner joint that is not load bearing.

Joist anchor. Used to join a joist or rafter to a beam or ledger in a tight, flush connection.

Toggle bolt. Used to secure object to a hollow wall. Spring-tension wings open to grip wall as bolt is turned.

OTHER JOINT REINFORCERS

These special hardware devices are used for stronger connections than those provided by nails, bolts or screws alone.

Molly bolt--A hollow-wall anchor, it’s en cased in a sheath that opens to grip the wall as the bolt head is turned.

Turnbuckle. Tightens wire used to support gate or fence post. Sleeve is turned to in crease or decrease tension.

ANCHORS

These metal connectors hold more securely than bolts. When they are carefully attached and painted, they blend unobtrusively with most wooden structures. Following are three common types of anchors.

Post anchor. Used to join a post to a concrete footing or slab.

Post cap. Used to connect a post to a beam, particularly where toenailing is not practical.

BOLTS:

Threaded rods that are usually tightened in place by turning a companion nut, bolts are used for heavy-duty work. Sizes are designated by diameter and by the number of threads per inch of length.

Lag bolt. Pointed screw end is driven into fixed joints in places where it’s impossible to use a nut.

Carriage bolt. Made with a shoulder to pre vent turning as nut is tightened. Sold with round or countersunk head.

Masonry bolt and anchor. As the hexagonal head is turned, the sheath around it expands to grip the inside of a predrilled hole.

T plate. A sturdy connector for joining wood at a spot other than an end or a corner.

Corner brace. Used for extra support of a load-bearing joint.

=======

BOLTS. Use bolts where the strongest holding power is required. Although some bolts have self-tapping threads, most are inserted through predrilled holes and secured with nuts. Cadmium- plated bolts stand up best to outdoor moisture. The bolt’s length should be the thickness of both lumber pieces plus ½ inch. Use a ¼-inch diameter bolt for lumber up to 2 inches thick; a 3 diameter for 3-inch lumber; a ½-inch diameter for 4-inch lumber.

Expansion bolts are used to fasten wood to plaster or masonry. A plug is placed in a hole drilled in the masonry with a carbide-tipped drill; it expands and tightens against the sides of the hole as the bolt is driven into it.

ADHESIVES. Glues and mastics are useful for securing odd-shaped joints, for reinforcing nailed constructions and for joining wood to masonry. Powdered or liquid epoxy-resin glues and pre mixed mastics especially made for out door use won’t be affected by rain and temperature changes.

METAL CONNECTORS. Galvanized fasteners such as post caps, flat braces of various shapes (L, T, Y or H , for example), framing anchors and metal clips are used where nailing is difficult or won’t provide sufficient joint strength. Post anchors and other types of masonry-to-wood connectors are em bedded in masonry as it’s being constructed or are attached to the finished masonry surfaces.

Finishes:

Depending on the effect desired, out door wood surfaces can be stained, painted or given a clear finish. Special stains and paints are available for use on outdoor masonry.

CLEAR FINISH. Natural weathering is often preferred for outdoor structures made of a rot-resistant wood like red wood or cedar, or a softwood that has been pressure-treated with a wood preservative. Most such woods weather to soft shades of tan to gray with varying amounts of sheen. The aging process can be simulated by using a mild caustic solution on the wood. New redwood , for example, can be darkened by brushing it with a solution of 1 part baking soda to 10 parts water.

If some protection against weathering is desired, use a clear sealer such as linseed oil, spar (marine) varnish or a clear penetrating finish. For best penetration, thin linseed oil with mineral spirits and apply several coats. Similarly, several applications of thinned marine varnish will reduce the tendency of the varnish to crack or peel outdoors. A clear penetrating finish needs renewal about every five years.

STAINS. The pigmented formulations called stains penetrate and color wood without obscuring its texture or grain. Stains are available in a wide variety of colors, some more transparent than others. Some non-chalking sealer-type stains contain ingredients that inhibit mildew. A gallon of stain will cover 350 to 400 square feet. Before applying stain, pre-treat bare wood with a clear penetrating wood preservative. Care fully applied stains will last five to seven years before re-staining is needed.

Special stains are made for use on old concrete surfaces or on new concrete that has cured at least six weeks. One gallon covers about 400 square feet, and two coats are usually needed.

PAINT. To get an opaque colored film on a wood surface, use paint. Available in either flat, semigloss or gloss finish, paint is the most moisture-resistant finish available for wood and offers the widest choice of colors.

Latex paint is a water-soluble formulation of pigment suspended in a natural or synthetic resin base. The quickest to dry of the exterior paints, it stretches and shrinks with temperature changes, thereby resisting cracking and peeling. Easy-to-apply alkyd paint, also resin-based, offers higher gloss and brighter colors than latex but dries very slowly. Oil paint contains pigment suspended in linseed or other oil. Slower to dry than latex, it’s more durable and requires renewing less often. Any paint’s life span depends on tempera ture extremes, wind, humidity and sun exposure. Generally, when properly applied, latex paint will last three or four years, while oil or alkyd paint will last seven or eight years.

Alkyd, latex and oil paints are specially formulated for use on masonry surfaces. Properly applied, all will last three to five years. Powdered portland- cement paints for masonry are less expensive but cannot be painted over with a resin-based product. When latex or alkyd paint is applied to a concrete floor outdoors, where traffic is limited, it can be expected to last about a year before repainting is necessary.

FOUNDATION See Concrete

= = = =

MORTAR JOINTS

As soon as the mortar joints in a masonry structure have hardened to a consistency that will retain a thumbprint, the joints can be shaped into final form. Finishing is not done just for esthetic reasons; the smooth, tightly compacted surface that results from shaping the mortar makes it more water and weather resistant.

After scraping off excess mortar from the joints with a trowel, shape the joints, vertical ones first. If your prime concern is waterproofing, choose a flush, weather or concave joint. A flush joint, made by troweling the mortar even with the face of the masonry, is the only style that creates no shadow. A weather joint, formed by troweling out the top of the joint, is aptly named because it sheds water so well. One of the commonest joints, the con cave, can be shaped to different depths by angling the end of a steel pipe slightly larger than the joint. A variation on the concave is the V joint, cut with a trowel or special tool.

A raked joint, which requires a square- cut implement to push back the mortar, is particularly good-looking but is susceptible to seepage. The so-called weeping or tapped joint, shaped by tapping on top of the masonry above to squeeze out mortar, creates a rustic effect.

FLUSH JOINT; WEATHER JOINT; RAKED JOINT; CONCAVE JOINT; V JOINT; WEEPING JOINT

= = = =

Glass

Safety is an important consideration when you choose glass panels for outdoor use. Check your building code to see if it specifies a minimum glass strength. Some codes require safety glass made of two layers with plastic or wire sandwiched between. Other codes allow tempered plate glass.

PANELS. Clear-glass panels deflect wind from a terrace or swimming pool without obstructing the view or blocking the sun’s warmth. Textured glass panels transmit light while maintaining privacy. Glass is such a fragile material that installation is usually left to professionals. Since glass is also costly, plan to use panels in stock sizes to reduce both initial cost and the expense of replacement. Make sure panel frames are strong enough to prevent wind damage.

BLOCKS. Transparent or translucent glass blocks, joined with mortar, are used in walls and screens. Blocks are made of two hollow sections sealed together; they come in 8-by-4-, 8-by-8- and 12-by-4-inch sizes. Glass blocks last indefinitely but are an expensive building material.

LATH See Wood

LIGHTS See Wiring

LUMBER See Wood

Mortar

A mixture of portland cement, sand and water with a small amount of lime or fire clay added for plasticity, mortar is used to bond stone, brick or concrete block. Dry-mixed mortar, sold in 10-, 25- or 50-pound bags at hardware stores and building-supply outlets, contains the correct ingredients in the right proportions and is ready to be mixed with water. Convenient for small jobs, it’s costly for extensive work. Masonry cement, a premixed combination of cement and lime to which you add sand as well as water, is available in 70- and 80-pound bags.

A good all-purpose mix for garden masonry consists of 1 part portland cement, 1 part hydrated lime and 6 parts builder’s sand. Stonework and retaining walls that are in contact with earth re quire a richer formula: 1 part portland cement, 3 parts sand and ¼ part hydrated lime or fire clay. With stone, use fire clay since lime causes discoloration.

Mix mortar in small batches to prevent premature drying. Using a wheel barrow, wooden box or just a square of plywood, mix the dry ingredients with a hoe. Add water gradually, blending it in until the mixture has a buttery consistency and slips cleanly from the hoe. Use the mix within an hour, adding small amounts of water and remixing if the mortar begins to harden.

NAILS See Fasteners

OUTDOOR CARPETING See Carpeting, Outdoor

PAINT See Finishes

PANELS See Aluminum, Asbestos, Glass, Plastic, Screening

PAVING See Asphalt, Brick, Concrete, Soil Cement. Stone, Tile, Wood

Plastic:

Because it’s impervious to rot or corrosion, plastic is a useful, versatile gar den-construction material. It appears in flat, corrugated or ridged panels, woven shade or insect screening, rigid pool molds, flexible sheets used to line pools and planters and to keep weeds out of walks, and in water and drainpipes.

SCREENS. Plastic shade screening, made of woven fibers, admits varying amounts of light depending on the tightness of the mesh. It’s available in many colors and is simply cut to size and stapled to a wooden frame.

POOL LINERS. Rigid plastic pool molds, made in many shapes and sizes, are strong, rotproof fabrications that can be set directly into the ground. Less expensive are pool liners of flexible polyvinyl chloride (PVC) reinforced with nylon. Flexible sheets of plastic are also used to underlay walks or loose brick and gravel to discourage weeds.

PANELS. The most common use of plastic in garden construction is in the panels that are built into overhead or fence frames. Plastic panels can be selected to provide whatever degree of shade is desired. Such panels are avail able in sizes from 24 to 50 inches wide and in 8-, 10- or 12-foot lengths. There are many colors and degrees of transparency, ranging from nearly clear to opaque. The light colors, which reflect heat, are more commonly used in warm climates. Corrugations and ridges give plastic added strength.

Plastic panels can be secured to a wooden framework overhead or in a fence with an aluminum-twist nail driven through a neoprene washer. The washer helps to prevent cracking of the plastic as the nail is driven. Space the nails about a foot apart. If you use corrugated panels, drive nails through the crowns, not the valleys. Plastic panels can be cut with a fine-toothed handsaw or power-driven carborundum disc.

PIPES. Plastic pipe has largely replaced copper or galvanized iron pipe in garden sprinkler and drainage systems because it’s more economical and easier to install. Water proof joints can be made simply by brushing a solvent on the end of a pipe and inserting it into a connector. But check your local building code; there may be restrictions on certain types or applications of plastic pipes.

PLYWOOD See Wood POSTS See Wood

PRESERVATIVES See Wood Preservatives

Reed and bamboo

Woven into mats, stalks of reed and bamboo both provide overhead shade at low cost. They are easy to handle, needing only a light supporting frame work to make a dappled shade pattern.

Woven reed is sold at plant nurseries and garden-supply stores in 23-foot rolls, 76 inches wide. It’s held together with wire that can be cut and re-twisted at any point. Either galvanized nails or 1-inch staples can be used to attach woven reed to a framework.

Woven bamboo, used indoors to shade screened porches, comes in rolls 3 to 12 feet wide and 6 feet long. There are two grades of bamboo—split and matchstick. Split bamboo is coarser and less regular than matchstick; it’s also stronger. Matchstick is more flexible and easier to fix to an overhead frame.

For a simple cover to shade a terrace, a roll of reed or bamboo matting needs no more support than a frame of 2-by-4s, but exposed cut ends should be covered with wood molding.

Reed and bamboo can also be used in fence sections as a windbreak. Treated with a wood preservative, the mat ting will last several seasons but it’s so inexpensive that most gardeners who use it replace it each year.

ROOFING See Aluminum, Canvas, Plastic, Reed and Bamboo,

Screening, Wood

JOIST See Wood

Sand

Grains of rock less than 1/12 inch in diameter, sand is one of the basic components of concrete, mortar and stucco. Brick or flagstone terraces and walks are often laid without mortar on beds of sand 2 or more inches deep.

In concrete, a coarse, gritty, dry sand with particles ranging up to 1/16 inch in diameter is best; this is often called builder’s sand. Masonry sand consists of finer particles more uniformly sized and is used in mortar and stucco.

Any sand used in concrete, mortar or stucco must be clean. To check, put about 2 inches of sand in a quart jar filled with water and shake it. Let the jar stand overnight. If the layer of silt that forms is more than 1/8 inch thick, the sand is too dirty to use. Never use beach sand in construction; its salt con tent prevents proper curing and bonding, and its sharp angular edges have been smoothed by the surf. You can tell so-called sharp sand, the kind you need, by rubbing a pinch near your ear. It should have a rasping noise.

Sand is available in 50- and 60- pound bags for small jobs, or, at lower cost, by the cubic yard. Store sand where it will stay dry; damp sand may upset your mixing calculations.

Screening

Woven screening made of wire or plastic filaments permits good ventilation while it shuts out insects. Though only special shade screens give controlled shade, any screening helps to reduce the glare of the sun.

Screening made of bronze, copper, plastic or aluminum has a long life expectancy if given reasonable care. Galvanized steel screening is strong and less expensive, but in time will require painting to prevent corrosion.

Where visibility is important, the thin strands of steel, bronze or copper screening give the best view. An occasional coat of varnish will prevent staining by bronze or copper. Plastic and aluminum filaments are thicker but they need no maintenance other than washing, though aluminum will be corroded by salt spray near oceans.

Wire screening comes in rolls from 16 to 72 inches wide, but the broader widths, 48 and 72 inches, are difficult to stretch taut before fastening.

Roof screening is simply stretched over a wood framework, stapled in place and further secured by narrow strips of wood nailed around the edges. Wall screening can be secured the same way, or you can use a special screen molding. For the latter, 3 lumber is partially cut along one edge so a thin strip can be removed, leaving a shallow recess. The screening is then stapled or nailed in this recess and the strip that was removed is replaced.

SCREWS See Fasteners

SLAT See Wood

Soil cement

Only ordinary garden soil and portland cement are used to make soil cement. This material provides a low-cost way to make hard paving that is appropriate for informal paths, parking areas, even terraces. The final surface, how ever, is more similar to hard-packed earth than to concrete.

A sandy soil is needed to create good soil cement; clay soil won’t harden satisfactorily. To test your soil to see if it will suffice, mix small samples in various ratios; from 1 part cement to 6 parts soil, up to 1 part cement to 10 parts soil. Stir in water until a mixture squeezed in your hand will hold finger- marks but not drip. Put the mixture into a makeshift mold, a tin can or plastic cup, and let it harden for a week. Then remove the soil cement from the mold and check its hardness.

If your soil is suitable, grade the area to be paved, for good drainage, and install wood strips to prevent edge crumbling. Break up the soil to a depth of 4 to 6 inches and take out any rocks or plant debris. Mix about 9 parts soil to 1 part dry cement, dumping the cement into small piles and mixing it in. Compact the mixture with a lawn roller. Sprinkle with fine mist as long as the water is absorbed. When the surface is almost dry, sprinkle and roll again. Continue light sprinklings as long as the surface absorbs water, usually four or five days.

= = = = = =

STONE SHAPES FOR GARDEN USE

above: ROUGH-CUT ASHLAR; QUARRIED RUBBLE; MOSAIC FLAGGING; SMOOTH ASHLAR; FIELDSTONE RUBBLE

Irregularly trimmed rough-cut ashlar is often used in broken courses for rustic structures. Smooth, carefully trimmed ashlar is laid in regular courses like brick.

This uncut stone is available as smooth natural fieldstone, river stone or as rougher quarried rubble, It’s well suited for informal dry wall construction.

Made by splitting stone into thin slabs, flagging is available both in irregular shapes and in regular-cut patterns, Its main use is for roughhewn paving.

= = = =

Sprinkler hardware:

Pipes, heads and valves are the main components of an underground sprinkling system. Various fittings join the pipes to each other and to the heads that deliver the spray. Valves regulate the water supply at its source and, sometimes, at each sprinkler head.

Sprinkling-system pipes can be made of galvanized iron, semirigid PVC (polyvinyl chloride) plastic piping, or flexible polyethylene plastic piping.

Galvanized iron is the most difficult to install; special tools are needed to work with it. In time, internal corrosion may restrict the water’s flow and make the system less efficient. But galvanized iron is not likely to be damaged by heat, rodents, freezing or wayward garden tools. In a high-pressure system galvanized iron is safer than polyethylene, which may burst, or PVC, which may leak at the joints. Iron pipes hold up well under the vibration of impulse- type spray heads.

Semirigid PVC pipe is available in lengths up to 20 feet that are easily cut with a hack saw. Fittings are attached with a solvent. Flexible polyethylene piping comes in lengths from 100 to 1,000 feet. Metal couplers and clamps join fittings and lengths of pipe. Either kind of plastic is less expensive than iron and easier to install. Plastic pipe does not corrode and it carries more water than steel pipe of the same size, since there is less internal friction.

Stationary and pop-up sprinkling heads are available. The former remain flush with the ground; the latter are lifted by water pressure when the water is on and drop back down when the water is turned off. Pop-up heads are more expensive than stationary heads and require higher water pressure but they water larger areas.

Most spray heads cover a circular area or some segment of one—three- quarter, half or quarter circles. A special type of head sprays rectangular or square areas; these overlap less than heads with circular patterns. Rotating impulse-type sprinklers throw bursts of water higher and farther, an advantage in sprinkling shrubbery or other tall plants. They are mounted above the ground and need high water pressure.

A variety of valves and timers are available to permit either manual or automatic control of the watering cycle.

STAIN See Finishes

Stone:

Available in pebble-like gravel and boulder-sized chunks, in consistencies ranging from porous sandstone to tightly compacted granite, stones never look out of place in a garden. Stones can be used to pave a patio or terrace, to build a wall or rock garden, or simply as at tractive ground covers. Their weight can make them difficult to work with, but once in place they are sturdy and virtually maintenance-free.

STONE SHAPES. Stones are sold in three forms: rubble, ashlar and flagging. Rubble is rough, uncut stone, quarried or taken from river and field. Large pieces of rubble—6 to 18 inches in diameter—are commonly used to build dry walls.

Smaller sizes of rubble stone, referred to as loose aggregates, include gravel, pulverized rock and crushed rock. They are used primarily as paving material. Gravel consists of naturally rounded pebbles from 1/4 inch in diameter to an inch or more. It’s often used as a drainage bed, but also pro vides a durable surface by itself.

Crushed rock, also called quarry stone, is man-made from larger rocks. The fragments range in size from ¼ of an inch to 1 1/2 inches. Its sharp facets interlock tightly, making it the most stable of the loose aggregates.

Dustlike pulverized rock is the smallest aggregate. It’s available as red rock, dolomite, decomposed granite or crushed brick, and generally is applied in two 3-inch layers, each moistened and compacted.

Ashlar stones are trimmed on all sides. Smooth or dressed ashlar stones are laid in regular courses like bricks and concrete blocks. Rough-cut ashlar stones are laid in irregular courses. Ashlar is available in common brick sizes (7½ to 8 inches long, 2 1/4 inches thick and 3¼ to 3½ inches wide) as well as in lengths up to 4 feet and heights up to 8 inches.

Flagging, or flagstone, is made by splitting stone into thin slabs. Thick nesses vary from approximately ½ inch to 2 inches; sizes range from 6 or 8 inches to 2 feet or more on a side. Used mostly for paving, flagging can be laid in regular patterns or irregular mosaics, on a bed of sand or on a concrete base.

VARIETIES OF STONE. All of these shapes—-rubble, ashlar and flagging— are available in various kinds of stone; granite, limestone, slate, marble, blue- stone and sandstone are the varieties that are most commonly used in gar den construction.

Granite is hard and nonporous. It’s difficult to cut and relatively expensive.

Common granite is grayish, but it’s often available in pink, white and green in textures from fine to coarse.

Limestone is not as hard as granite, but is strong enough to be used for most garden construction, including paving (it can support at least 60 tons per square foot). Limestone is porous and absorbs water quickly; it’s a favorite for rock-garden construction. Lime stone varies in color from dark gray and green to cream and off-white. It’s chalky and easily cut.

Slate is hard and nonporous. It’s naturally stratified and thus can be easily split into flagstones. It’s available in shades of black, green and gray.

Marble is hard enough for many gar den uses. Sold as smooth-cut ashlar, it’s one of the most expensive construction materials, but it’s also available in less costly chip form, used for gravel- type walks and pathways. Most marble is cream or pinkish white, but many other colors are available, from black to green to purple, depending on where the stone was quarried.

Bluestone is available in many colors besides blue, including pink, cream and red. Its rough surface is often used where nonskid paving is required.

Despite its misleading name, sand stone is nearly as strong as limestone. It’s made up of sandy material (usually quartz) bonded by a natural cement such as silica. Its color ranges from yellow and white to buff and dark brown.

BUYING STONE. Flagging is sold by the square foot, rubble and ashlar by the cubic yard. To determine the amount of flagging needed for a paving job, measure the area and add an additional 10 percent for breakage and re placement. To determine how much rubble or ashlar you need, multiply the length of the area to be surfaced by its width (in feet) by the desired depth (in a fraction of a foot), then divide that number by 27 (the number of cubic feet in a cubic yard). Use the same formula to compute the amount of material needed for a wall, substituting height for depth.

INSTALLING STONE. Paving stones are laid on a base of soil, sand or concrete. In areas of stable soil, the stones are laid out on the lawn in a pattern and their outlines marked with a shovel. Then they are removed one by one, the sod is removed to the depth of the stone or slightly less, and the stones are replaced.

Stones can be laid on a base of sand as shallow as 2 inches in mild climates; up to 6 inches is advisable where severe freezing is common. Like bricks, paving stones are set on the sand and additional sand is brushed across them to fill the joints. Stones at least 2 inches thick are desirable to prevent cracking.

Stones as thin as ½ inch can be mortared to a poured concrete base. When the mortar has set, the joints can be filled with sand or grout.

Stones used in walls can be set dry or in mortar. The weight of the stones and their interlocking facets hold a dry wall together. A dry wall can be set directly on the ground or on a 6-inch layer of gravel. The stones are tilted inward to give the wall greater stability; bonding stones running the full width of the wall at intervals will add strength.

Mortared stone walls generally are set on concrete footings. The mortar mix that bonds the stones should be relatively thick so it won’t seep out of the irregular joints.

Tools needed for working with stones include a trowel, mason’s chisel, stone mason’s hammer, shovel, hoe and level. A rake is needed to spread loose aggregates. Wear protective goggles when cutting stones.

Stucco:

For durability and appearance, a layer of concrete called stucco is troweled over the exterior of wood or masonry structures. Stucco mortar is made of sand, portland cement and lime, differing from bricklaying mortar only in the smaller lime content. A basic stucco recipe, enough to cover about 24 square feet, consists of 200 pounds of builder’s sand, 47 pounds of portland cement, 12 pounds of lime and 6 gallons of water.

Stucco is generally applied in three layers over metal lath. The first layer, the scratch coat, is ¼ to /8 inch thick. It’s applied to the lath and is scored so the second layer, also ¾ inch thick, will adhere. The final coat, about 1/8 inch thick, is the cosmetic coat that can be textured as desired. Tinted stucco cement is available in several colors for use in the finish coat. Stucco can also he painted with masonry paint.

Special tools needed for stuccoing include steel and wood trowels, a mortar board, a long wire brush, plus a hoe and wheelbarrow for mixing. Other materials used include metal flashing, met al lath, wood furring strips, building paper and nails.

If you mix and apply stucco, wear a long-sleeved shirt, gloves and goggles; the lime in the mix can irritate unprotected skin and eyes.

Tile:

Made of hard-fired clay, tile is among the most durable of construction materials. Tile is used to make outdoor payers, pipes for drainage systems and ho low blocks for walls.

DRAINAGE TILES. To divert water from a damp area, use red drainage tiles. These are cylindrical in shape, 4 to 6 inches in diameter and 1 foot long. They are placed end to end, unmortared, just below the drainage level of the soil and are covered with roofing felt or roofing paper, then with layers of gravel and sand in which excess water can disperse.

WALL TILE. The block-shaped hollow tile used in building walls can also be used to make ornamental planters. It’s commonly available in 8-by-8, 4-by-16 and 8-by- 16-inch face sizes, in thick nesses of 4, 6, 8, 10 and 12 inches. The glazed finish can be a variety of colors.

PAVING TILE. Unglazed patio, quarry and mosaic tile are used as payers; they have a slightly textured surface to make them safe underfoot.

Patio file is 3/4 to /8 inch thick and comes in irregular sizes about 6-by-6, 6-by-12 and 12-by-12 inches, in shades of red and buff.

Quarry tile is more regular in shape (and more expensive) than patio tile. Its edges form precise right angles, so a smoother surface is possible than with patio tile, which has rounded edges. Quarry tile is available in many colors in sizes 4-by-4, 4-by-8, 6-by-6, 9-by-9 and 12-by-12 inches.

== === ===

LUMBER LENGTHS FOR DECKS AND OVERHEAD SUPPORTS

When designing a framework and calculating lumber needs for a garden deck or shelter, your first considerations should be structural soundness and safety. In general, flooring must be able to support a minimum of 50 pounds per square toot, including 10 pounds of dead weight in the structure itself. Roofing must support at least 30 pounds per square toot, possibly more where snowfall is heavy.

Post lengths and beam spans are the easiest to calculate. As a rule of thumb, a 4-by-4- inch post 8 feet long or less will support anything up to 8,000 pounds. But as post length increases, so do bending forces, reducing the weight that the post can carry. So a 4-by-4 post will support only 2,600 pounds if it’s 14 feet long. A 4-by-6-inch post up to 8 feet long will carry 14,000 pounds.

The distance a beam can span is determined by its width: a 4-by-4 can span 4 feet, a 4-by-6 can span 6 feet, on up to a 4-by-12, which can span 12 feet. Beams should be placed with the wider side vertical.

For joists and rafters, the chart below gives the maximum length for each commonly used size of lumber, depending upon the spacing between boards. In each instance the length that is given equals the maximum span be tween supports. The greater the number of joists or ratters used in a given space, the longer each can be. It’s often less expensive to space boards closer together and make them longer than to increase the size of lumber used, because the cost of a board is based more on its thickness than its length. For example, you may come out ahead by using 8-toot 2-by-4 rafters that are spaced 16 inches apart instead of 8-toot 2-by-6s that are spaced 32 inches apart. Spacing measurements are from the center of each board. As with beams, joists and rafters should be placed on edge.

MAXIMUM LENGTH OF LUMBER

Lumber Dimensions (in inches) | For Joists: | Spacing between Boards (center to center)

== == ==

Mosaic tile, ¼ inch thick and 1 to 2 inches wide, is sold in a variety of de signs, patterns and colors. It comes mounted on squares of paper or mesh, precisely spaced; a square of the small tiles can be laid in one operation, with the paper or mesh removed later.

The larger paving tiles can be laid in a smooth bed of sand 1 inch below grade, or they can be set with mortar or mastic on concrete, wood or brick.

Tile paving is luxurious; its cost is two or three times that of brick. Tile is also somewhat fragile and can be shattered if it’s carelessly handled or improperly installed.

Tools needed for installing tile include a notched tile trowel, level, rule,

hoe, shovel, rake, mallet and wheelbarrow in which to mix mortar. Paving tiles are cut with a tile cutter, which is used to score a tile so it can be snapped like a piece of glass. Such cutters usually can be rented wherever tiles are sold. Curved cuts can be made with a mason’s tool called a nipper.

Outdoor tile is set with a special mortar mix, sold in 20- to 50-pound sacks. When the mortar has cured for at least 48 hours, tile grout is used to fill the joints between the tiles, forming a watertight surface.

Wire fencing:

For strong security fencing, chain-link and woven or welded-wire mesh are sold in patterns that are difficult to climb, keeping small children and pets inside and garden pests out. Wire fencing is strong, long lasting and easy to maintain. Fencing made of aluminum wire is rustproof; that made of galvanized steel is rust-resistant. For a more decorative look, plastic-coated steel wire is made in a wide variety of colors including green and black.

Select woven or welded, wire fencing according to the size of the mesh openings, the height (up to 6 feet) and the gauge (diameter) of the wire. The usual gauges for home use are 11 to 15½, though heavier 6- to 9-gauge fencing is available. Wire fencing is sold in 50- foot rolls or in bales of 10 or 20 rods (a rod is 16½ feet). Some types of woven- wire fencing have crimps between the upright stays to compensate for expansion and contraction with seasonal temperature changes.

===

LUMBER SIZES

Lumber is sold by thickness and width, in two-foot increments from 8 to 20 feet long. The thickness and width are given in the dimensions the board had when it was cut from the tree, or the “nominal” dimensions. When the board is milled, its size is reduced by the amount of rough wood cutoff. As the sap and moisture dry out, shrinkage reduces its size even more. Thus, a nominal 2-by-4 is actually P by 3.5 inches; the actual size may be fractionally larger or smaller than that de pending on the kind of wood. The accompanying chart lists, in inches, the nominal size and actual dimensions (in parentheses) for several common lumber sizes.

If you need a board that is a full 1 inch or 2 inches thick, you can specify, but it will have to be milled to order and will be expensive. It’s simpler to accept wood in the size it actually comes in, making measurements for your project accordingly and ignoring the nominal sizes. If you want a size not stocked, say a 2-by-5, you usually can have it cut at the lumberyard from the next larger size.

=== ===

Chain-link fencing is sold by wire gauge (usually 9 or 11 for home use) and height (36, 42 and 48 inches). For enclosing swimming pools, chain-link fence 6 feet high is available. This fencing is generally sold in 50-foot rolls, complete with such hardware as steel posts, gates, hinges and top rails.

Installation of chain-link fencing is difficult and should be left in the hands of professionals. Lighter fencing, with wooden posts, can be installed satisfactorily by amateurs. Special tools needed include a posthole digger and a fence stretcher or block-and-tackle.

Metal picket fencing, sold in 36-, 42- and 48-inch rolls, needs no posts; it’s simply pushed into the ground. In 16- and 22-inch heights, it’s used primarily to identify the boundaries of flower beds and borders.

Wiring:

Two kinds of systems are available to supply electricity to garden lights. One uses standard house current of 120 volts, the other a stepped-down 12 volts. Cables that carry 120 volts are potentially dangerous outdoors and must be protected with heavy weatherproof conduit.

Some electrical codes permit 120- volt plastic-sheathed cable to be buried directly in the ground. In other areas, the buried cable must be enclosed in metal tubing called conduit—either a thin-wall metal such as aluminum or a heavy-wall metal such as galvanized steel pipe. Usually, conduit must be buried at least 18 inches deep to reduce the chance of its being accidentally cut when the garden is spaded. It’s wise when laying any cable to make a diagram showing where it’s located, rather than to rely on memory.

In either case, the National Electrical Code specifies that 120-volt receptacles be connected to a device called a ground-fault interrupter (GFI). If hazardous current leakage occurs, the GFI immediately cuts off the electricity.

Low-voltage wiring, sheathed in waterproof plastic, carries only 12 volts; it’s virtually shockproof and therefore far safer to handle, even when the current is on. The wire can safely be buried in a shallow 4- to 6-inch trench without extra protection but care must be taken not to cut it accidentally with garden tools. Kits for low-voltage wiring include a transformer that reduces the current from 120 volts to 12 volts, plus several lighting fixtures and up to 100 feet of wire.

Wood:

Many kinds of softwoods are available for garden construction, so it’s important to choose the type that will provide the appropriate strength and appearance for your project. Certain woods have characteristics that are particularly suited to specific garden uses, from simple planters to elaborate gazebos. While planning your project, however, keep in mind that some woods can be bought only in the regions where they are produced.

Softwoods such as Douglas fir and yellow pine, with their close-grained strength, are especially useful in heavy construction work. But cedar, redwood, spruce and white pine are slightly softer with a straighter, more predict able grain, and are therefore easier for the average gardener to saw and shape. Cedar, cypress and redwood are particularly decay-resistant and, along with spruce, more resistant to shrinking, swelling or warping than other types of softwoods.

The decay-resistant woods, especially redwood cut from the heartwood near the center of the tree, don’t re quire treatment with preservative or paint, and may safely be sunk in the earth or otherwise exposed to constant moisture without danger of rotting. Other softwoods, however, should be treated with a wood preservative if they are to be used outdoors.

Softwoods may require periodic re pairs and maintenance—painting and other refinishing—and even then they may in time deteriorate to the point where they must be replaced. The life expectancy of the wood will be determined in large part by where it’s used and how well it’s maintained.

WOOD PRODUCTS. Available wood products range from sawdust and bark chips to shingles and laths to boards, timbers and sheets of plywood, not to mention railroad ties and telephone poles. Most forms are classified according to their quality. A chart showing how lumber and plywood is graded is on shown.

The smallest bits of wood—sawdust and chips—are used as mulches and ground covers. They tend to wash away in the rain and need a barrier to hold them in place. They are available at garden centers.

Buy lumber at a lumberyard or well- stocked building-materials store so you can be sure of finding the sizes and grades you need. Among the thin strips available are laths, 4- to 8-foot rough- cut strips 1½ inches wide and 3/8 inch thick. Lath is used for trellises to sup port climbing plants and for overheads and lath houses to protect tender or shade-loving plants.

For fences, ready-made pickets come in many shapes, from those with the traditional triangular tops to some with more intricate variations. Also used in fencing are grape stakes, 3- to 6-foot lengths of redwood that are about 2 inches square. Some gardeners split or saw grape stakes in half lengthwise to save wood.

Plywood can be used to build gates, fences, birdhouses and a host of other projects. It most commonly comes in 4- by 8-foot sheets 5/16 to 3/4 of an inch thick. Only exterior or marine-grade plywood should be used; otherwise the plies may come apart even if the structure is sealed against moisture.

For paving patios and paths, decay- resistant cedar, cypress or redwood blocks and round-cut sections about 4 inches thick can be placed randomly on a sand base. Useful for steps, edgings and low walls are railroad ties and landscape timbers, treated with a preservative so they will last many years.

Logs and rails are often available for building rustic furniture and fences. Used telephone poles, sometimes avail able from salvage dealers, are suitable for long retaining walls. Poles can be stacked lengthwise or cut into shorter segments to be placed vertically.

BUYING WOOD. Lumber is generally priced by quantity. Since boards come in many different sizes, a standard measure is achieved by converting the actual dimensions of the wood to an imaginary board foot 12 inches wide, 12 inches long and 1 inch thick. To compute board feet for any piece of lumber, simply multiply width and thickness in inches by length in feet, then divide by 12. When you buy lumber, note that the actual size of the wood you receive will be slightly less than the nominal size because the dimensions are reduced during the milling process. This difference may vary anywhere from to ½ inch. A 4-by- 4-inch block of wood , for example, will be only 3½ by 3 1/2 inches.

HANDLING. To keep boards from twisting and warping, store them flat on crosspieces so air will circulate around them. Keep lumber under cover to shield it from moisture.

Wood preservatives:

Any wood that is to be used in garden construction, if it’s not naturally rot-resistant, will benefit from treatment with wood preservative, a chemical that helps prevent decay and insect dam age. A preservative properly applied will protect wood for 10 to 35 years, depending on soil and climate conditions. The best protection comes from the commercial application of the preservative under pressure; dip-treating at home is economical but somewhat less effective.

Care must be taken in the selection and use of preservatives. Some are toxic to plants and hazardous to the person who applies them.

The oldest commonly used preservative is creosote, which leaves a dark, unpaintable stain and is very toxic. Pentachlorophenol-based mixtures don’t leave smell or stain, but they are also toxic to plant life; they should be used with care, especially near prized specimens. Copper sulfate, which is good on unseasoned wood, leaves a blue stain. Copper and zinc naphthenates are nontoxic and odorless, al though copper naphthenate leaves a pale green stain.

Commercially pressure-treated wood is widely available and is recommended for garden-construction projects. You can also buy preservative solution in quart or gallon containers at building- supply stores and apply it yourself. The more preservative the wood absorbs, the better it will be protected. It’s especially important that the freshly cut ends of lumber be soaked in preservative, since the end grain is very susceptible to rot damage.

Spraying preservative gives poor coverage, and it may irritate the eyes and damage nearby plants. Apply it with a brush or, best of all, fill a trough and soak the wood in it.

Wrought iron:

A malleable, corrosion-resistant metal, wrought iron can be hammered and welded into gates, posts, railings and other garden ornaments that will easily outlast their builders. But true wrought iron has become rare, except possibly at antique dealers. Most modern iron work is milled steel, subject, to corrosion if it’s not protected with regular applications of primer and paint.

Such ornamental ironwork, in pre fabricated designs, is available from steel fabricators and garden shops. It can also be made to order, although the cost is high. Supporting posts are anchored in fresh concrete, cemented in holes drilled in existing masonry or anchored in flanges bolted to either wood or masonry.

===

GRADES OF GARDEN-CONSTRUCTION LUMBER

SOFTWOOD GRADES

(Including such woods as cedar, cypress, fir, pine and spruce)

SELECT: For quality indoor furnishings.

STRUCTURAL: Beams and posts graded according to strength.

Construction ‘Top-quality structural lumber.

A Virtually flawless. Used in the finest cabinet and furniture work.

B A high-appearance lumber with smooth sides and faces; may show infinitesimal blemishes.

C Has minor defects that can be concealed with a coat of paint.

D Has small, tight knots that can be concealed with paint.

COMMON: For general Construction purposes.

No. 1 Warp-free, though it may contain any number of solid knots. Excellent for outdoor furniture.

No, 2 May have coarser defects such as loose knots, discoloration and checks, Good for general garden construction.

No.3 Small knotholes, pitch, checks, even warpage. Inferior sections may have to be cut out.

No. 4 Low-cost, low-quality construction lumber with many knotholes and coarse blemishes. Adequate for informal fencing.

No. 5 Inferior lumber riddled with large knotholes and other major defects.

Standard Slight defects, although strength is similar to construction grade.

Utility An inferior structural grade. May be unsatisfactory for some garden construction; should be used only where other structural members add support. Not recommended for fencing.

Economy Poor quality structural material. Should be used only for bracing or wooden crates.

REDWOOD GRADES

Clear All-Heart Superior quality. Highly decay resistant and free of knots. Primarily used for fine furniture.

Clear High-quality wood. May show small knots and minor blemishes. Excellent for outdoor benches and tables.

Select Heart High-strength, all-heart redwood. May contain slight defects such as torn grain and small, sound knots.

Construction Heart Good, general-purpose commercial-grade lumber. Recommended for posts, decks and small garden projects. May contain some large, tight knots.

Select Free of imperfections but less decay resistant than heart grades.

Construction Common Good, all-purpose construction lumber. May contain sapwood, tight knots and discoloration.

Merchantable Contains loose knots and knotholes. Heartwood and sapwood are both included in this economical grade.

EXTERIOR PLYWOOD GRADES

A-A Exterior -- Smooth, paintable, premier quality. Used where the appearance of both sides of the panel is important.

A-B Exterior -- Excellent for painted surfaces or for natural finishes where the appearance of one side is slightly less important than the other. Both sides are sanded smooth although the back of the panel may show tight knots.

A-C Exterior -- For use where the appearance of only one side is crucial. Face will be smooth-finished but the reverse may show 1-inch knotholes, tight knots and other defects.

B-B Exterior An outdoor utility panel with paintable surfaces for use where appearance is not important.

B-C Exterior Reasonably smooth surface on the face; knotholes and limited splits on the reverse.

C-C An industrial product for use where appearance is not a factor.

Unsanded surfaces are rough and hard to paint.

Prev. | Next

Articles in this Guide are based on now-classic Time-Life Encyclopedia of Gardening Series from the 1970s ... a timeless series, some titles of which are still available in libraries and bookstores ... see our Amazon Store for purchasing options.