From the standpoint of low maintenance, we

should gauge furniture value first of all by its construction; how long

it will last without breaking or falling apart. Then we should determine

how long various treatments will preserve the wood from decay due to

moisture or insects. Thirdly, we need to look at what finishes will preserve

the desired color or patina of the wood the longest, and which of these

means less work in keeping the furniture clean and presentable. Unfortunately,

these practical considerations are often superseded by fad and fashion

before which there is no defense.

I can tout the advantages of one furniture

style over another, or one finish over another until I’m blue in the

face, and if fashion or fad dictates something else, something else it

will be, except for those sensible enough who don’t mind taking the road

less traveled.

Determining Furniture Construction

For example, some Chippendale chairs of great value have backs that

are too fragile to even score a C for low maintenance. George Grotz,

in his The Furniture Doctor, goes so far as to say that “Chippendale

chairs are fragile pieces that you either have to keep in glass cases

or continually repair.”

The reason he says that, not altogether tongue-in

cheek, is that Mr. Chippendale liked to dress up his furniture with all

kinds of fancies popular at the time—ornate carvings, or in the case

of some of his chair backs, with intricate cutouts in the back rails.

Structurally, these ornate holes in the wood did nothing but weaken it,

especially when a really stout lord of the manor leaned back while sitting

in one.

Length of the Grain

An even worse design flaw in my opinion is the Hepplewhite shield-back chair. Especially in less expensive imitations of the originals, these chair backs are glued together from several short curved pieces of wood and will not hold up to heavy use. In fact, whenever you see any wood furniture design that incorporates round or excessively curved lines, be ware. Most curved crest rails on chairs, particularly the round balloon- back Victorian chairs, are structural disasters. As Desmond Gaston says in his Care and Repair of Furniture, such chairs should never be lifted with only one hand at the middle of the crest rail, but with two hands, one on each back upright. Better still: Avoid furniture with structural pieces of wood in round or smartly curved forms, unless the wood is bent to form the curve, as in a good Windsor chair.

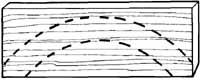

The reason is that wood’s structural strength derives from what carpenters refer to as “long grain” wood. If you cut a board lengthwise with the grain—the only way you can cut a long board—it has strength. Try cutting a thin strip of wood off a wide board cross-grained, and you will find the subsequent stick or strip very weak—you can snap it in two over your knee. “Short grain” has no tensile strength.

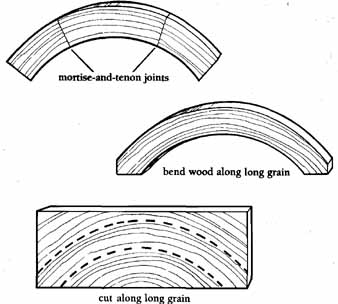

Keeping that in mind, take a look at the grain in any board. It usually runs fairly straight down the length of the board. If you cut a curved or rounded piece out of that board, as for a crest rail or whatever, you have a comparatively weak piece with lots of short grain. Any sharply rounded piece cut from a board will be extremely weak. Therefore to maintain long-grain strength in a curved form, you either have to bend the wood or tenon two, three, or more slightly curved pieces of wood together, each piece maintaining as much long grain as possible. Strength in the latter case depends on how well the glue and tenon joints hold up over the years, and the usual answer is, not so well in a chair back.

A weak wood curve: a weak short grain; will break

easily

Three stronger wood curves.

There is a third and best way to get a curve and that is to use only naturally curved-grain wood for curved shapes. Thus in James Krenov’s masterful pieces of cabinetry, invariably curved pieces are made of curved grain. You can see the grain flow with the curve. Handcrafters in wood always keep their eyes open for such boards in lumberyards or limbs or tree trunks in the woods. For example, the best old farm wagon sled runners are cut from ash trunks that grow out in a short curve at the base of the tree. Rockers on rocking chairs should come from curved-grain boards or from curved branches thick enough to cut into rocker boards, If a rocker is cut out of a straight-grained board, it is bound to be weaker.

Joinery

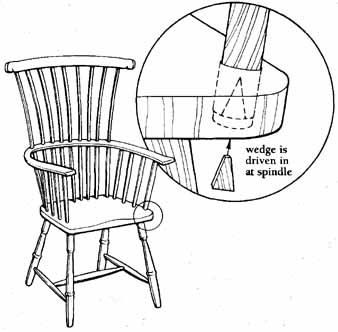

A second characteristic of wood that affects structural soundness is its tendency to swell and shrink with changing humidity. Therefore, how pieces of wood are joined in furniture is of crucial importance. If there is no allowance for wood movement, the joints will shrink and loosen or swell and break. Chair rungs and back spindles are the worst sinners in this regard. If you simply drill a hole in wood and glue a rung or spindle in it, in time it will loosen and pull Out and/or break off. On good furniture, extra measures are taken to lock the joint. To use Thomas Moser’s current furniture as but one example, rungs and spindles go all the way through the chair seat or back rail, then they are spread at the socket with a wooden wedge—the same technique that’s used to keep a hammer handle in its head.

Locking a furniture joint.

At the very least, rungs and spindles should be heat-dried down to 8 percent moisture or lower (which is lower than the prevailing humidity in a house) and then seated tightly in their holes. The spindle or rung then swells a bit in ordinary room humidity, locking it almost irrevocably. Even if room humidity in winter gets down to where the wood shrinks a bit, it will not shrink enough to break the glue joint. When heat-dried rungs or spindles are used with green seat or leg wood, as in good handmade Appalachian ladderback chairs (such as you can find for sale in Berea, Kentucky, where Berea College has long been supportive of traditional crafts), the joints are the strongest possible: the green wood shrinks and the heat-dried spindles or rungs swell a little. No glue is used at all. This was (and with the Amish still is) the way mortised-and-tenoned barn beams were joined so permanently together in traditional barns. After 200 years, sometimes the only way to take such a joint apart is to cut it apart with a chain saw.

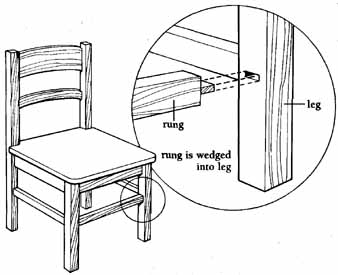

You can’t tell by looking at a chair if the rungs and spindles have been joined this way. Price may be an indication—a Moser chair, so made, will cost around $500 and after you have fussed with cheap chairs half a lifetime, you know the price is worth it. You can, however, check for through-wedges. Cabinetmakers who use them let them show proudly where they come through the seat or leg or back rail, handsomely sanded down, the wedge a dark line across the face of the spindle. Usually this is a sign of good furniture. But the ultimate Cadillac, or maybe I should say Rolls-Royce of a chair rung joint is a hidden through-wedge. Instead of boring a hole completely through a chair leg, which of course weakens the leg a bit more than a hole only partially through, the hole is bored about halfway, wider at the rear than at the opening. Then a slot is made in the rung, the wedge started in the slot, then the rung inserted, wedge first, into the hole. As the rung is driven home, the wedge spreads the rung end to fit the hole and lock it in place. It takes great skill to do this right, because once the rung is driven in, you’re going to have a hard time pulling it out again if the fit is not right.

Wedging a chair rung.

Another never-failing joint for spindles is seen today only on some good handmade furniture, though it was often used on Windsor chairs a century ago. The back rail on a good Windsor is all one piece, bent to the proper curve and the ends through-wedged into the seat. The intervening vertical spindles were through-wedged at the top. But where these spindles join to the seat, instead of through-wedging, old-time cabinetmakers cut slots in the back of the seat board and left a knob on the end of the spindles. The spindles were then inserted into the slots and the slots closed by one of a number of ways. It was then impossible for the spindles to pull out because the knobs on each spindle end were larger than the slot. Such spindles last for generations without glue. They may get loose, but they can’t come out.

In carcase construction (any furniture in box form like cabinets and chests), there are many ways to join the corners, from simple gluing to intricate dovetailing. Simple gluing of a butt end of a board to the side edge of the one perpendicular to it, without any kind of joinery notching the boards into each other, is the least durable. Miracle glues we may have, but they won’t keep wood from swelling and shrinking. At least dowels (pegs) ought to accompany gluing, if not grooves that allow horizontal boards to fit into vertical ones in some way that spreads the stress of the joint to the wood as well as the glue. Countersunk metal screws are never as strong as dowels but will hold wood together fairly well in cheaper furniture. The problem with screws as with wonder glues is that the temptation in using them is to avoid good joinery methods instead of using them in combination with such methods. And if good joinery methods are used, there is no need for screws or wonder glues. Incidentally, in repairing furniture, using nails and screws hardly ever gives long-lasting results. Wood and glue alone will make a stronger and more durable repair every time. Nails will only cause problems for your furniture repair shop when you finally take the piece there for proper fixing.

With plywood and veneer, you might get away with cheaper joinery methods, maybe even glue alone, because these products do not move—swell and shrink—as much as solid wood. We tend to look down on good veneered furniture as inferior to solid wood, which it is in strength and repairability. But laminated wood does not warp like solid wood can. And you can cut more gracious curves in laminated wood without worrying about short grain.

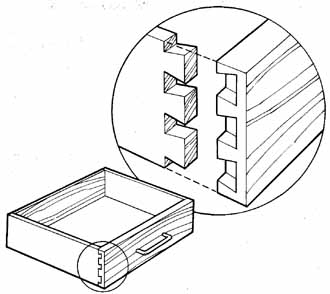

Most furniture-makers would agree that the best carcase joint of all is the dovetail. Trapezoidal-shaped notches are cut into one edge of a board and matching notches are made in the edge of the board that it is joined to at right angles. The two slip together so that you see a row of little dovetails on one side and, if you go around the corner of the joint, so to speak, you’ll see a row of little rectangles. Sometimes, depending on fashion, the dove tails are hidden, but today they speak so much for quality that furniture makers display them grandly, often using contrasting woods to make them show up better. Dovetail joints can be machine made, and almost all better furniture will have at least the side joints of drawers dovetailed. Hidden, machine-made dovetails (cut with a power router) are weaker than hand made ones because the router groove cuts away about a third of the dovetail’s thickness.

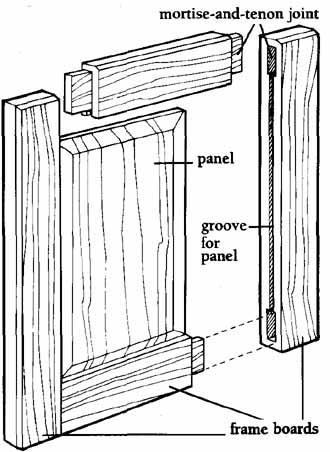

In good frame-and-panel construction, as in a door or paneled cabinet, the frame boards are mortised and tenoned into each other at the corners, and a groove is cut all along the inside of the frame. The panel fits into these grooves and is not glued. Rather, the panel “floats” in the grooves, having enough room so the wood can swell and shrink without splitting the wood. This is especially necessary on an exterior door ex posed to the weather.

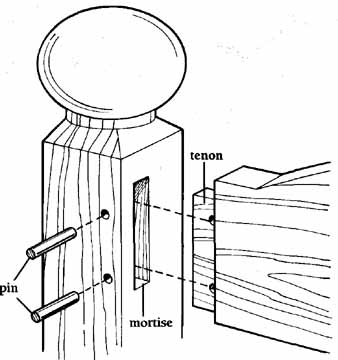

Mortise-and-tenon joints are also used to join braces to legs, chair back splats to uprights, like the “ladders” in a ladderback chair, and table aprons to table legs. This kind of joint provides a much greater area for gluing than the usual round hole of a rung or spindle and so is much stronger. Sometimes in handcrafted furniture, the artisan will put a wood pin or two through the mortise-and-tenon joint, which locks it even more permanently.

Dovetails at drawer corners.

“Floating” frame-and-panel construction.

On really good furniture, the cabinetmaker will almost always use a clear finish so that the pins, the mortise-and-tenon joint itself, and any other kind of fancy joinery will show clearly. Beware of furniture that is stained so dark and heavy that you can’t see grain or joinery details. Before I knew better, I bought a set of spindleback chairs that loosened in three years. The uprights on the back were indeed through-wedged to the seat, but the wedges had not been properly driven in, nor did the uprights reach completely through the seat. Close inspection showed that the ill-made joints were hidden under a varnish-stain glop. I should have been suspicious anyway, because the chair legs were reinforced under the seat with little metal braces. In quality chairs, these braces are entirely unnecessary.

The best furniture in terms of structural strength is what is called knockdown furniture, most often exemplified by the trestle table. Knock down furniture, as the name indicates, comes apart easily and is favored by people who know they are going to change residences often. Because it is not glued or screwed together, knockdown furniture must depend on structurally sound and skillful joinery, keyed together with wedges. If you try to wiggle a knockdown trestle table and it doesn’t wiggle, you know you are in the presence of first-rate cabinetry. The piece is made to swell and shrink in season with no worries about breaking glue joints. I have a little spice cabinet that remains fairly tight though it has no glue in it and comes completely apart. The mortising, dovetailing, and pegging necessary in such knockdown furniture, however, takes so much handwork that it is rarely done commercially even in small handcraft shops.

Another detail to look for in furniture design is the triangle. Oddly, except for a few mavericks, furniture incorporating triangles has not been popular for several centuries, the rectangle being the approved geometric unit. But try this experiment sometime: Nail four boards together in a rectangle, with one nail at each corner. You can easily move it into any parallelogram shape you desire. Now nail three boards into a triangle with one nail at each corner. It won’t budge. Using triangles, you can build stout furniture even with relatively flimsy components. The moral: If you see chairs, tables and sofas with triangular bracing, you know they have inherent strength.

Mortise-and-tenon joint with wood pins.

Arms Add Strength to Chairs Chairs made for use around the table do not usually have arms. And such chairs must rely almost solely on the joints between the back and the seat for strength. Since the weight of the person leaning against the chair back is more toward the top of the back, the leverage engendered puts great stress on the joints at the seat. And this is the main reason so many chair backs come loose. This problem is greatly alleviated if the chair has arms because the arms act as an extra brace higher up on the chair back, greatly relieving the stress at the seat joints. The moral of the story? For greater durability, buy chairs with arms even if they don’t fit under the table. The armrests add considerable comfort to sitting, too. |

Can Leaning Back on a Chair Weaken It It is not altogether correct to say that a chair can be ruined by leaning back in it on the back two legs. With cheap furniture it certainly is true, and more might be ruined than just the chair. But a well-made chair should hold you safely on two legs as easily as four, as Appalachian makers of good ladderbacks love to demonstrate. One maker has even developed a trick of hopping around on one leg of his chairs just to show how strong they are. |

Other Signs of Quality Furniture

• Is the chair seat flat or is it carved out to take the shape of the buttocks? The flatter the cheaper, the more deeply sculptured, the higher the quality.

• Are carvings or inlay work well done or sloppy? Such decoration in itself neither adds to nor detracts from the durability of the piece, but it does indicate care and skill in the cabinetmaker.

• Are the inside and underside corners of cabinets, chests, etc., reinforced with glue blocks? They should be.

• Open the drawers of bureaus and look inside. Are there dust panels between drawers? If so, this is almost always a sign of quality furniture.

• Lay the extension leaves of a table you want to buy on top of the table. Do they match the tabletop precisely? On good furniture they will. On poor furniture, they might not. Also, both the top and bottom of table leaves should be finished exactly the same way. If not, the side with less finish will pick up moisture or dry out at a different rate than the other side, causing warping.

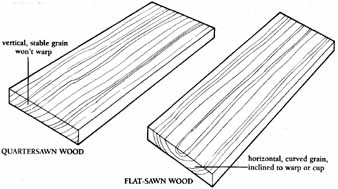

• Look through the butt edge of a board on your piece. The more vertical the grain that runs through the thickness of a board, the more stable it will be. The more curved or horizontal the grain through the thickness, the more it will be inclined to warp. The former is called quartersawn, the latter flat-sawn. Quartersawing wood wastes some of the log and is not commonly done anymore, but it is superior structurally.

Edge grains in wood boards.

Upholstered Furniture

In upholstered furniture, the best seats have coiled springs tied together with lots of fabric webbing. But such springs demand a heavy framework to hold them from breaking loose after a few years, especially when Uncle Filbert breaks his diet and drops 245 pounds of flesh into them. You might be better served with light furniture, and the cheaper flat intertwining S springs. They are not as comfortable and hopefully not as inviting to Uncle Filbert, and so less likely to need costly repair work. Rubber and other light, springy kinds of webbing to support seats alone are not practical no matter how cheap. They soon sag out of shape. Better to have a solid wood seat with foam rubber cushions.

Vinyl coverings for upholstery are the easiest to clean and maintain. Whether you want to cover richly upholstered furniture to keep it clean is a matter of opinion, I suppose. What is the use of having grand furniture if it is never seen except when you throw a party (which is just when it needs a covering the most)? It reminds me of people who buy expensive cars with a beautiful front grille and then cover the grille with an ugly bug screen. But a good compromise in furniture is to cover chair and sofa arms with little pads of an attractive, matching pattern. The arms are what get dirty quickest and where the most wear takes place. And armrest coverings can be easily washed.

Feel through the upholstery on a chair or sofa you want to buy. Is the wood ample at the bottom rail of the frame? It should measure at least 2 by 2 inches. Grab the top of one back upright in one hand and the front of the arm diagonally opposite to it in the other hand. Pull toward each other. Then pull the two arms toward each other from the front. In both cases if there is a lot of give, the joints are no doubt bad. Keep this little technique in mind when buying used pieces. If there is much give in a new piece, then it is really bad stuff.

On used furniture, look for worm holes. By the kind of mysterious obstinancy human beings are regularly capable of, a dent or gouge in furniture may be unforgivable, but worm holes give added value. But if the worm holes are active, there’s nothing attractive about them. Look for frass (fine sawdust) under a piece of furniture—it indicates active worm holes. Spraying a few times in the holes with an insecticide usually gets rid of the borers, but if they have been in the wood a long time, they may have weakened it badly. Furniture that sits near fireplaces is often the first to be infested with borers. The reason is most logical. The borers come in with the firewood brought in to burn. The best remedy is to bring in wood only as needed for the fire. Borers will chew in most woods but seem to favor beech, birch, and elm. And there’s a kind that loves to eat wicker furniture.

Which Woods Make the Best Furniture?

Generally speaking, hardwoods make more durable furniture than softwoods. Hardwoods, again generally speaking, come from broad-leaved trees and softwoods come from coniferous trees. Oak, cherry, walnut, and mahogany are prime hardwoods for furniture but many others are used including beech, elm, birch, ash, gum, hickory, pecan, plus many exotics such as teak and ebony. In fact, there are very few hardwoods (including all the fruitwoods) that are not used for furniture. In the softwoods, white pine is the principal furniture wood used in this country, although others might well be substituted. Good white pine furniture might last as long as good walnut furniture, and some from colonial times is certainly as valuable today as some finer furniture of that age. So softwoods are not necessarily inferior.

Generalities are hard to make where wood is involved. One must first specify how or where each type of wood is used in furniture. In colonial times, for example, no respectable country carpenter would use pine in the chair rungs or anywhere else strength was important. Pine chairs had pine seats. Legs might be oak, rungs almost always ash or hickory. A cupboard on the other hand, being largely made of wide flat boards, might be all pine and plenty strong enough for the purpose. But because it was soft and easy to work it was rarely used for tabletops, which took much abuse. Pine has no distinctive grain, but the colonials invariably painted their furniture and did not give a hoot about grain anyway. Wood grain was one of the most common sights in their world so it had little standing decoratively.

One finds beech, birch, and gum often used in cheap furniture, but this is not a slur on the strength or durability of the wood itself. These are common woods and so cheaper woods, but they can make good furniture from the low-maintenance point of view. Because beech, birch, and especially gum have little in the way of showy grain, they can be stained to resemble more expensive woods. Thus they get the reputation of being cheap imitations of good furniture. That being the case, their presence in a piece of furniture may indicate less quality—not because of the wood’s inherent characteristics, but because the furniture-maker was not intent on making quality furniture when he used them. If he intended to take the time to make a good chest of drawers, he’d use cherry or walnut. Thus today, a factory-made chest of white ash stained to look like walnut or cherry, or passed off as white oak, could be very moderate in price and cheap in construction—and therefore rank far down the list of low- maintenance furniture. The same ash, cut and assembled by an accomplished cabinetmaker like James Krenov, could rank at the top of the list—and be very, very valuable to boot.

Look, for example, at upholstered furniture from the first part of the twentieth century, if not earlier. If the back legs are beech or birch instead of mahogany, oak, or walnut like the wood that shows in front, the piece is invariably of lower quality. The wood doesn’t make it lower quality, but only indicates that less time was taken in quality construction, and that quite possibly, cheaper springs were used.

In other words, except for specific structural demands, like the supple tensile strength of hickory and ash for spindles, rungs, and bentwood, the kind of wood used depends in large part upon whatever fashion dictates as desirable at the moment. Thus white oak goes in and out of fashion—it was all the rage at the turn of the century and is so again today. As a woodworker I dislike it because it is open pored and requires more work to get a smooth, glasslike finish. And because it is so hard. Planer blades dull twice as fast on white oak as on black walnut. But white oak (unlike red oak) is very strong and even where (as in table legs) you must mortise holes that are quite large and reduce the actual thickness of the leg by half, oak will stand up to it where walnut might not. Incidentally, in such a case a couple of dowels that require only two small holes might make a better joint for low maintenance than a large mortise-and-tenon joint, even though it is now fashionable to think of doweling as cheap factory joinery and mortise and tenon as quality handcrafted work.

Cherry is a fairly hard wood too, but excellent for carving, which is one reason why so often antique carved furniture in Chippendale or whatever is cherry. Although many carvers prefer softer woods, like bass wood, cherry (as is true of many fruitwoods) can be carved with good crisp detail and does not split out in carving into the grain. Cherry of course, is also considered extremely beautiful in color if not in grain.

Black walnut and Honduran or African mahogany are not as hard as cherry or maple but have both the color and grain the human eye has always found irresistible. Their presence in furniture almost always de notes high quality.

Many exotic woods are used by handcrafters in furniture-making and their use denotes quality furniture, whether or not the wood itself is all that great. For instance, American woodworkers have a current penchant for brash sassafras. But some exotic woods, like teak, have inherent high quality. Teak is extremely hard and oily and will decay hardly at all, even if left out in the weather.

Maple can be both a common furniture wood and exotic (such as curly maple or bird’s-eye maple). The appearance of these maple grains in furniture indicates high quality, since no woodworker would commit such valuable wood to cheap work. Bird’s-eye maple is almost always found on old furniture as veneer. Veneer can be high maintenance since a dent or gouge might go all the way through it. Also glues, especially before about 1950, were not what they are now, and older veneers may delaminate due to glue failure. But, as mentioned earlier, veneered furniture does not tend to warp as solid woods do and so should not be sneered at.

Plain hard maple is an excellent furniture wood and takes a superior finish. Being lighter in color than cherry or walnut, it can be stained to almost any color desired.

How to Tell Woods Apart You can’t by eye. Black walnut has a dark brown to purple natural color, unlike any other American wood. If you see it unfinished, you can tell it rather easily. Raw cherry wood has an orangeish-pinkish tint to it that is also fairly easy to identify. Beyond that, however, only practice and experience can tell, and then even experts are often fooled unless or until the wood is examined microscopically. Clever wood finishers can make cheap woods look very much like expensive ones. Also the way the log is sawed—flat-sawn or quarter- sawn—can make the same wood look quite different in grain. As with jewelry, you must usually rely on the honesty of the furniture-maker or dealer. And hope they know what they are talking about. You can make walnut and mahogany look like each other, gum look like cherry, even maple look like cherry. The point is, if the piece is well made, does it matter if it is really walnut or really mahogany? If you pay cherry prices for gum you have of course been cheated, but all else being equal, one table will probably last as long as the other. |

Finishes for Wood Furniture

Because my son makes new furniture professionally and sometimes repairs old furniture, I get a lot of phone calls meant for him inquiring about better ways to finish furniture. Since I consider myself a little knowledgeable on the subject, I used to make the mistake of trying to answer the questions myself. Before long I realized most callers were not really interested in what I had to say but were only looking for an excuse to trumpet their own favorite concoctions. It appears that anyone who has ever lifted a paintbrush is an expert on wood finishes, just as anyone who has ever lifted a pencil is sure he can write a book if only he had the time. So when I’m asked about varnish, shellac, lacquer, oil, and how to solve the state of the economy, I have a stock answer. I pause a moment or two, which I hope denotes to the caller that I’m mulling over the case he or she has presented. Then I say: “I can think of several possibilities and I bet you can, too.” Then they tell me just what possibilities they can think of, and I learn more than they do. Summing up: There’s an almost unlimited number of ways to finish wood and any of them are fine if the result is what you want. For instance, sheep dip makes a nice finish if you are striving for a grain color of deep cobalt blue. Honest.

Even the experts delight in disagreeing with each other. Consider tung oil, for example. To listen to certain ads on television or to certain woodworkers, tung oil comes directly from the hand of God for our everlasting happiness, by way of Homer Formby’s refinishing secrets (Formby’s being a quality brand name in tung oil).

But Marc A. Williams, senior furniture conservator at the Smithsonian Institute indignantly challenges some of Formby’s notions in the June 1986 issue of Rodale’s New Shelter magazine in a letter to the editor: “It is totally inappropriate to ‘feed’ wood with oil products,” he writes. “Lin seed oil and tung oil are absorbed into a surface and react with oxygen in the air to polymerize and harden. With time they become difficult to remove, can darken almost to black, and attract dust and dirt.” He further states that Formby’s refinishing secrets are based on age old “myths.”

Then George Grotz comes along (my favorite expert, cited earlier) in his book The Furniture Doctor and disagrees with both. He doesn’t think oils’ darkening wood is such a problem, but on the other hand, he is positively disrespectful to the worshipers of tung oil, calling it nothing but floor sealer at a higher price. In some instances that might be right, but one must be careful dealing with experts. Grotz goes on to describe tung oil as being made by “squeezing the juice out of resinous pine trees in Louisiana.” As probably thousands of his readers have told him by now, he appears to be inadvertently confusing turpentine with tung oil, which comes from the seed of the tung tree. Almost all finishers (even Grotz) agree that tung oil is a good finishing product, but Tage Frid, another expert, says it darkens wood much less than linseed oil does in his book Tage Frid Teaches Woodworking.

Who’s right? They all are in one way or another. We are dealing with art as much as science. The idea is to keep everyone slightly confused, and when all else fails in that goal, the experts start talking about some esoteric formula, perhaps from sixteenth-century China, that uses seedlac varnish scraped off banyan trees that is diluted with urine from a Tibetan llama. Of course, it reaches its potential only if you put on 32 coats and rub it between coats with rice chaff moistened in castor oil. And of course again, seedlac varnish is available only from two hermits who live in the forests of northern California.

This whole business of furniture finishing is a game humans love to play. How many times have I seen a homeowner look over a newly delivered piece of furniture from the store and nearly have an apoplectic fit upon finding a scratch so small and out of the way he almost needs a magnifying glass to find it. He then pounces upon the hapless delivery- man, demanding his money back or another piece of furniture. This very same homeowner, on another occasion, shows me a newly purchased piece of “antique country” that appears to have been dragged out of a barn. He proudly points out the cracks, gouges, peeling paint, and mouse gnawings that make the piece “authentic.” The truth is we finish furniture (or refrain from finishing it) mostly for reasons of fashion and in the long run little of the art and science involved has anything to do with maintenance, although we determinedly pretend otherwise.

In discussing low maintenance and furniture care, we must first admit that plain old bare wood, rough sawn or sanded, will last forever within the shelter of a house, as long as the atmosphere is reasonably dry and bugs or animals don’t eat it. All that wood finishes can do is make the furniture easier to keep clean and perhaps preserve a certain desired color of the wood. If the truth be told, preserving the wood itself is more in the capabilities of environmental control than in finishes. Finishes can do very little about moisture because they do not penetrate far enough to have much effect. If you really want to control swelling and shrinking in wood, use humidifiers and dehumidifiers, as any museum curator will tell you.

With that caveat, I will proceed through the various clear finishes with an eye to maintenance, not beauty or fashion. We think of these finishes—shellac, lacquer, oil, varnish, and polyurethane—as separate and distinct substances, but as a matter of chemical fact, they overlap. Specific finishes may contain both oil and varnish or shellac and lacquers. The lac in shellac and lacquer originally stood for the same thing—a bug, or the excretions of this parasitic insect. Today, commercial lacquer is something quite different from that old Chinese lacquer. The first “varnishes” came about when shellac was boiled with linseed oil. Polyurethane is really a varnish that may contain cottonseed oil rather than linseed oil to which tough plastic formulations have been added. The main purpose of all these materials is to enhance the beauty of the wood in some way. But some are better than others in terms of maintenance, as I hope to make clear here.

Shellac

This is one of the easiest finishes to apply. It dries fairly fast, is very clear, and takes polish very well. French polishing is usually done on shellac. Liquid shellac does not store well, and it is better to buy the dry flakes and mix or “cut” your own as needed with denatured alcohol according to directions. Shellac readily dissolves in alcohol and so is easy to remove if you want to apply another finish. By the same token, it is not a good topcoat for furniture, especially tabletops, because alcohol will dissolve it. Water is also a bane of shellac—a wet glass makes white rings on it. And if shellac is applied in an excessively humid atmosphere, it may develop a whitish blush. Better to use shellac for low maintenance as an undercoat, as a sealer between a stain and a varnish, or as a sealer for varnish alone. Unless labels say otherwise, you should not varnish directly on stain. Some people mistakenly think it is wrong to varnish over shellac; most professionals do it because shellac can be rubbed smoother than a first thin sealer coat of varnish and is cleaner than sanding sealers.

Lacquer

Lacquer today is almost always nitrate cellulose and acetone in varying formulations. It is much tougher than shellac and dries very fast. In fact, it was developed to answer the need of assembly line factory furniture that required a very quick-drying finish. Some of these lacquers dry almost instantaneously upon hitting the wood or other surface you’re covering, so you have to spray them on if you don’t want to leave brush marks. Brushable lacquers are available if spraying is not your strong point, but even with these, quick drying can make brush marks a problem. Most store-bought, mass-produced furniture is finished with this lacquer. Though it is more durable than shellac as a topcoat, it suffers from some of the same drawbacks: water causes white stains, and waxing the lacquered surface only delays the appearance of the white stains a little longer. Such stains, like white rings from wet glasses, are, however, rather easy to remove by smearing a little mayonnaise on them, waiting a few minutes, and then wiping off.

Factory-applied lacquer also won’t hold up well to frequent contact with human skin. Where arms or hands rub a lot on tabletops, chair arms or back rails, the lacquer finish will soften, get muddy, and then dry rough and ugly. Then you have to remove the mess with lacquer thinner and apply a good polyurethane varnish or a hard carnauba wax.

Since there are so many variations in formulas and in woods them selves, not to mention people’s attitudes, I’m aware that nearly anything I say can prompt an exception, but there’s one hard-and-fast rule about lacquer that’s agreed upon by all: Do not apply it over an oil or varnish finish. It won’t dry. Since so-called sanding sealers have become popular to use to seal wood before other finishes are applied, they are often used under lacquer. I suppose it’s a matter of taste, but this somewhat dulls the high-gloss effect we use lacquer for, and some finishers have observed that under such a finish, wood pores may turn whitish after a few years. Skip the sealer and apply three to four coats of lacquer instead for better effect. Practice makes perfect, and the high gloss achieved is much easier than French polishing on shellac.

Chinese lacquers and seedlac varnish lacquers that come from the lacquer or varnish tree are more like shellac than commercial lacquer. Furniture finished with them is beautiful, but they must be painstakingly applied in several thin coats. Unless you are going to make a serious hobby out of wood finishing, such finishes are beyond practical interest and beyond the scope of this guide.

Oil

Oils are the easiest materials for a good practical furniture finish in my opinion. You can more or less smear them on any old which way and then wipe them off. How long you should wait before wiping them off is a matter of opinion, even in this simple operation. This, of course, means you have plenty of leeway and not to worry. Oils were one of the earliest finishes, and linseed oil, from the seed of flax, continues to be one of the most-used ingredients, not just used alone as a finishing for wood, but in combination with varnishes and paints as well. Many materials that go by fancy names like “antique finisher” or “aging polisher” are little more than linseed oil and petroleum distillates with perhaps some drying resins or other driers to speed up drying time. Oils dry slowly, especially linseed oil, which in fact never dries completely in pure form. Tung oil, its leading competitor for Favorite Oil of the Century, dries faster but is still slow. Other admixtures of oils and resins, called generically “Danish oil,” dry better to a harder, more durable finish than pure linseed oil. Pure oils, because they dry slowly, do catch dust, which can be rubbed in with subsequent applications. Over the centuries this may or may not lead to a significant darkening of the wood, which may be desirable.

Most finishers, except those like the Smithsonian curator I quoted earlier, believe that oil finishes improve with age. The ones who idolize linseed oil claim, after an ancient adage, that a linseed-oil finish needs to be renewed periodically for years, perhaps forever, each thin coat deepening the luster and beauty of the finish. This is a matter of taste, not maintenance. But an oil finish is much easier to repair than a lacquer one, all finishers agree. And that is what mainly concerns us here.

Don’t use oils in drawers or bookcases. On hot days, oiled wood may bleed a little and clothes or paper might get stained. Also, to some noses, oil in an enclosed drawer or cabinet gives off a kind of rancid odor.

Varnish

Varnishes contain oil, usually linseed oil, with resins and other sub stances added to make tougher, stable, more durable finishes than shellac or lacquer. For tabletops especially, varnish ought to be the preferred finish for low maintenance. Because of the oils in them, varnishes dry rather slowly compared to shellac and lacquer. This is good from the standpoint of avoiding brush marks, but bad from the standpoint of attracting dust and lint on the wet surface. But drying times get shorter and shorter with new formulations coming on the market. Whatever varnish you choose (or any other finish for that matter) always apply it in a room temperature of 70° to 80°F for best results. Varnishes give a slightly yellow cast to the wood (or stain) but it is a toss-up whether this is an advantage or disadvantage. Again it is a matter of taste. Varnishes are more resistant to heat, water, and alcohol than other finishes.

POLYURETHANE

Polyurethane varnishes need a category separate unto themselves. They are varnishes, but the ingredients and formulations are more complex and the refining process more sophisticated, resulting in products that wear well, resist scratches, and are almost impervious to household chemicals, detergents, alcohol, boiling hot water, and vegetable stains. They apply easily with urethane foam applicators (no brush marks) and dry fast and so, for all these reasons, are of particular interest for low maintenance. (One drawback of polyurethane is the shiny, sort of plastic gloss that results. And another is that such a tough finish is harder to repair if it does get scratched deeply)

There are so many urethane and polyurethane formulations on the market that even the experts give up and say that for the average layperson the best advice is to stick to good brand names and avoid cheaper products. Basically, the main ingredient in the oil-base kinds (which is what you should use for furniture) is good old linseed oil, although it might also be soybean, safflower, or cottonseed oil. When the word alkyd is added to the description of oil-base polyurethanes, and this is true in paints and enamels as well as clear finishes it means they contain a synthetic polymer binder derived from linseed or other vegetable oils. The difference is slight. Alkyds improve adhesion and reduce cost. The different blends and formulations between oils and alkyds are legion. Don’t worry about it too much. But, especially for exterior furniture, linseed oil—base alkyd polyurethanes are generally considered more durable than soybean or safflower oils. The latter, especially safflower oil, are less darkening, however.

There are both gloss- and satin-finish polyurethanes. The former contain silicates to gloss up the finish a bit. These silicates give the glossier varnish a harder finish, making it more durable and preferable for outside use over the satin. Satin finishes hide imperfections in the finish, glossy polyurethanes make them more visible. Polyurethane varnishes do not take the kind of rubbing I describe below. Buffing alone, however, will increase luster, even without wax—another low-maintenance plus. As with any finish, several thin coats are better than two thicker ones. And as with regular varnish, if you use polyurethane as a first coat sealer under a second coat of polyurethane, thin the first coat with mineral spirits for better penetration. Label directions should specify details.

No Finish at All Wood furniture in some cases, especially where blemishing stains are not likely, does not have to be finished at all. My son has a little bedside stand he made, and its bare wood has displayed its beauty now for several years, none the worse off for no finish at all, and to his eye, more beautiful without any. As the famous cabinetmaker James Krenov says: “Left natural, elm and ash are beautiful; they look fine hand-planed, or planed and then sanded very lightly so as to give a misty effect. Any finish put on such wood will detract from, rather than add to it . . . .For whatever reasons—smell, color, feel—wood as it is after being worked with skill is for me a matter of pride, almost a boast. Many of the pieces I make are intentionally of wood that need not be sanded—or even finished at all.” (From The Fine Art of Cabinetmaking, by James Krenov) As much as I agree with Krenov (and my son), a good lacquer or varnish finish will help keep warping at a minimum and enhance the beauty of most furniture woods. |

Stay with One Brand

A smart rule to follow, whatever kind of finish you decide to use, is to stick with the same brand name when applying two or more different materials. If, for example, you decide to go the complete route of starting with bare wood and applying a filler, then a stain, then a sealer, and finally topcoats—or any combination thereof—it’s best to stay with the same brand name because of possible slight variations in formulas between different manufacturers. Behlen is one of many good companies, and I mention it only because its many products are available conveniently by mail, through the Garrett Wade catalog of woodworking tools and supplies. Minwax products and Deft products I have found to be very good, and Watco finishing oil a nice substitute for pure linseed or tung oil. And as I said at the beginning of this section, I’m sure you know of some even better. All three of them are readily available in most hardware stores.

When the Finish Is Not Quite up to Your Expectations

Theoretically, whether you use shellac, lacquer, or varnish for a finish, if you do things right, the finish should be the finish. Unfortunately, this is usually not the case, and for a real professional look, you need to finish these finishes by rubbing. Most of us will leave brush marks in shellacs and lacquers and specks in varnish. (Always finish furniture in as dust-free an environment as possible.) The specks may be dust or sawdust particles or tiny bits of resin that gather in varnish sometimes, especially after the container has been opened a while. Or the finish might turn out too shiny to suit you, rather than possessing that deep glowing luster you fancy. Sometimes you can lightly sand out surface roughness, brush marks, or runs; then wipe with a lint-free rag and apply one more topcoat. But the proper way is to do a professional rubbing job, which is not difficult, and which, in addition to smoothing and cleaning the surface, also removes undesired shininess.

Get some 3M brand abrasive paper from your hardware store or auto- supply store, in 400-, 500-, and 600-grade grit. Fold a small section of the paper around a rubber block. Dip it into a tray of mineral spirits and gently rub with the grain in as long a stroke as possible. You have to be careful not to sand through the finish, which is easy to do at the edges. Keep the surface wet with mineral oil while rubbing and wipe away glop that gathers on the surface with a paper towel and clean mineral spirits. Start with the 400 grit and repeat with the 500 and 600, always very gently. Try to avoid overlapping as much as possible and look at the surface against the light to see any skips. When all surface imperfections have been removed, wipe clean and let dry completely. You can leave the surface as is, if you like a matte finish or buff it for a deeper luster. If you want more glow, use wax.

There are other ways to polish furniture, but they are all harder than this method. And since traditionally they are done with shellac, they are not particularly low maintenance.

Wax or Oil?

Once you have furniture finished to your liking, you’ll want to keep it that way, and this is where the biggest argument ensues among experts and non-experts. Should you wax or should you oil? The answer is: it depends. It depends who you ask. If you opt for wax, it should be a hard wax—with a goodly proportion of carnauba in it. A good waxing twice a year is sufficient. With furniture polishes (mostly linseed oil with lemon scent), you go over the furniture every week or so, but it is far easier than waxing. Waxes build up; furniture polishes darken. A good wax on lacquer will inhibit blushing and water spots somewhat; furniture polish won’t. The best choice in my opinion is Renaissance Wax. It cleans and protects (even against alcohol) and does not obscure the beauty of the wood. It’s what most museums use to maintain their priceless treasures, and that’s good enough for me.

Repair Sticks

Scratches in varnish and oil can often be rubbed out. Crinkles, cracks, and crazes in old shellac or lacquer can be obliterated by dissolving these finishes—alcohol for shellac and acetone or lacquer thinner for lacquer— and allowing them to flow together and harden again, but this is very tricky business. (Low-maintenance buffs should stick with oil or varnish.) Deeper scratches can sometimes be obscured with furniture retouching crayons, which are about the same things the kids use for coloring books but come in colors more likely to match wood tones.

But for filling and hiding dents, gouges, and deep scratches, the best option is what are called “lacquer sticks.” They are the consistency of crayons, too, but are actually shellac with drying and solidifying resins added, of about candy bar shape and size. They come in most wood colors used in furniture. You melt a little of the lacquer stick onto a hot knife (300°F is perfect) and let the liquefied shellac then flow into the hole or gouge. About any knife will do; you can even buy electric ones just for this job. When the filler solidifies again, you can sand it smooth and cover with any topcoat. If sanding is too risky on furniture already finished, there are other products to smooth the surface without harming the surrounding area, like Abrisol and Burn-In-Balm from Behlen. All the products mentioned in this paragraph are available from the Garrett Wade catalog.

Painted Wood Furniture

Though the prevailing mood is for clear finishes that show the natural beauty of the wood, there has always been a modest interest in painted furniture. In terms of low maintenance, paint on furniture has the same advantages and disadvantages as paint on walls. Chips, gouges, and mars will show more visibly on painted furniture than on clear-finished furniture, and that is just about the whole maintenance story.

In most cases, whatever is used (even enamel paint unless label directions specify otherwise), whether it needs an undercoat or not, or whether the wood ought to have a filler applied before paint is applied to smooth and close the pores (read label directions to find out), the paint ought to be covered with a clear finish. Lacquer is sometimes used for an extremely high-gloss finish on paint. Better for low maintenance is to seal the paint with shellac and then top-coat with a satin varnish. The shellac sealer is important, even on tough, hard enamel, because otherwise the varnish can lift some of the paint color and give the finish a dirty cast; the varnish “pulls off the paint” as a finisher would say.

Oil-base enamels seem to be the preferred (though by no means only) paints used on furniture. A favorite is Waterlox. Some painters will mix a tung oil additive or something similar to make the enamel flow better and dry quicker. You can also mix Waterlox and similar products alone with dry pigments to get any color you desire. But this subject opens up a vast range of information that has little relevance to maintenance pro or con.

Metal and Plastic Furniture

Chrome dinette sets are very much out of style right now. They are, or were anyway, fairly low maintenance. The biggest problem: tears in the plastic seat and back covers. The only handy way to mend a tear was with tape—ugly to say the least. But the chrome frames of the chairs and the plastic-topped chrome tables will last a long time without half the upkeep of wood.

Metal furniture moves in and out of fashion as continuously as the rising and falling of hemlines. Brass beds can be very big one year and ho- hum the next. I think this inconstancy is connected more with age than with era. At some point in our lives (not always the same point with everyone), brass beds make the heart throb and two years later make the mouth yawn. The same with iron beds.

Brass and copper can be lacquered to prevent tarnishing. Brass beds and other brass furniture are usually factory finished this way. If or when lacquer begins to peel from the metal it can be removed quite easily with denatured alcohol and the surface then re-lacquered. Use a transparent metal lacquer. Do not use a metal polish or cleaner on a lacquered surface. To clean, simply dust or wipe with a damp sponge.

Stainless steel would make heavy and costly furniture, but think how beautiful this burnished surface would be. Usually where ordinary steel is used in furniture, as in the office or on the patio, it is painted, and the paint wears and chips with use in a manner we would not tolerate in the living room. But if steel were treated like good wood, burnished and finished with clear oils and polishes and gone over regularly with polish to prevent rust and renew the shine, how beautiful it would be, and with far less maintenance than wood. Metals have grain, too, and laminated metals, as for example Damascus steel, have very beautiful grain indeed. But such furniture awaits a new twist in postmodern styles.

The plastic lucite furniture of the ‘50s was wonderfully indestructible stuff. Because plastic can be molded to any shape or curve, it is much more amenable to the human body than wood, and many times more stable. But modern man associates (often justifiably) plastic furniture with mass produced junk and continues to hunger after wood. Somehow, low maintenance to the contrary, I’m glad.

Rabbeted and glued corner joint.

Doweled and screwed corner joint.

Cabinets and Shelves

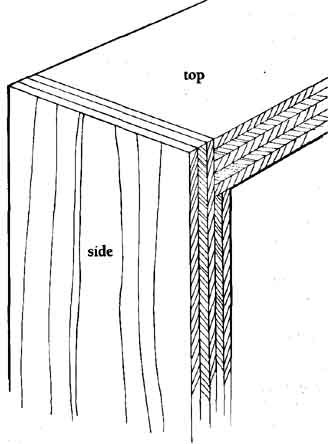

What has been said about wood furniture applies to wood cabinets as well, with one exception. Cabinetry often calls for rather large expanses of flat wood, as in doors, tops, or sides. In solid wood, large flat expanses are hard to keep from warping and so in this case, low maintenance applauds the use of plywood with birch or other hardwood facing. Plywood makes very strong boxwood construction since it cannot rack, and only in joining corners is there a problem. A screw, nail, or even dowel will hold well in the face of plywood (driven through its thickness). But when you try to insert any of these into the edge of the plywood (directly into the layers of laminated wood), they will not hold well at all. Thus, corners should be rabbeted and glued—the rabbeting makes more corner area to glue.

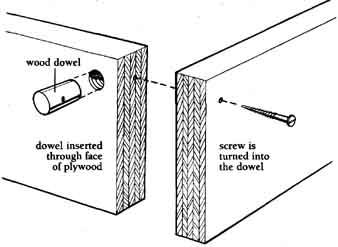

Carpenters have a little trick to make the screws hold in the laminated edge of the plywood. They ascertain where the screw will go into the edge, then they insert a dowel through the face of that edge so that the dowel will intersect the screw going at right angles into the laminations. The screw then screws into the dowel, not just into the laminated edge, and holds solidly.

Where plywood less than ¾ inch thick is being used, cabinet corners should all be backed on the inside with glue blocks to hold the corners solid.

In choosing kitchen cabinets for durability clear-finished wood still gets the nod from me over anything painted because paint will show blemishes quicker than clear-finished wood. Cabinets covered with plastic laminates are easier to clean than wood, although a smooth factory finish on good hardwood cleans nearly as easily. (If water drops turn white on the finish, you don’t want the cabinet.)

A feature to look for in kitchen cabinets is a door pull backed by a metal or other long-wearing plate of some kind. Ours are of antique brass (you don’t have to be forever shining them) and they keep fingers and rings from blemishing the wood when you open a door or drawer.

The best low-maintenance cabinet door latch is a magnetized hinge, with no latch at all. When these first came out, the little magnets in the hinges, which not only keep the doors closed but pull them closed if they are left ajar, would pop out after about seven years. Improvements generally have solved this problem.

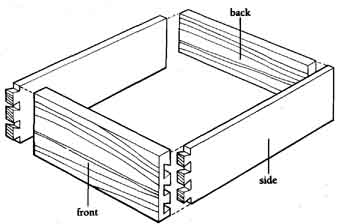

In checking kitchen cabinets, another good indication of durability is the way drawers are made. On the best ones, the fronts are dovetailed to the sides to endure generations of pulling. The bottoms of the drawers are held in grooves (dadoes) in the bottoms of the front and side—not glued—and the backs sit on top of the bottoms to which they are only lightly tacked. All this leaves the drawer bottom free to “float” in its grooves. It can contract and expand with changing humidity without pushing the drawer sides out so that they stick.

Drawer construction.

Bookshelves

Bookshelves are rather straightforward cabinets. Shelf boards really ought to be dadoed into the side boards, not just butted up and nailed or screwed. At any rate, remember that books are heavy, and shelving using 1-inch boards (which are really ¾ inch) should have a support at least every 2½ feet. Any less support than that and the shelf can sag under a full load of books. Incidentally, book collectors say that glass-enclosed book cases are not better for books. They may keep dust from accumulating, but in open shelves there is more air circulation to ward off mildew-related problems, which is a bigger problem for books than dust.

Prev.: Low-Maintenance Walls and Ceilings

Next: Low-Maintenance Appliances