Soapmaking--A Simple Miracle To Perform Yourself In Your Kitchen

According to Roman legend, soap was discovered after a heavy rain fell on the slopes of Mount Sapo (the name means " Mount Soap" in Latin). The hill was the site of an important sacrificial altar, and the rainwater mixed with the mingled ashes and animal fat around the altar's base. As a result of this fortuitous coincidence, the three key components of soap were brought together: water, fat, and lye (potash leached from the ashes). As the mixture trickled down to the banks of the Tiber River, washerwomen at work there noticed that the mysterious substance made their job easier and the wash cleaner.

Over the centuries the basics of soapmaking have remained essentially unchanged from the Roman prescription. To this day in parts of rural America soap is being made much as it was in ancient Rome: out of potash, rainwater, and animal tallow. Even commercial soap is manufactured by much the same process. Other than obvious differences in the scale of the operation and the use of automated equipment, the chief innovations in the commercial product are the substitution of sodium hydroxide for potash and the use of a variety of vegetable oils as supplements to the animal fats.

Homemade soaps can duplicate or improve on the commercial product, usually at considerably less cost.

Scents, coloring agents, and decorative effects are all within the scope of home soap makers who also have the advantage of knowing exactly what ingredients are in the soaps that they produce. The result is that more and more people are trying their hand at making soap, often experimenting with ingredients to devise their own favorite blends.

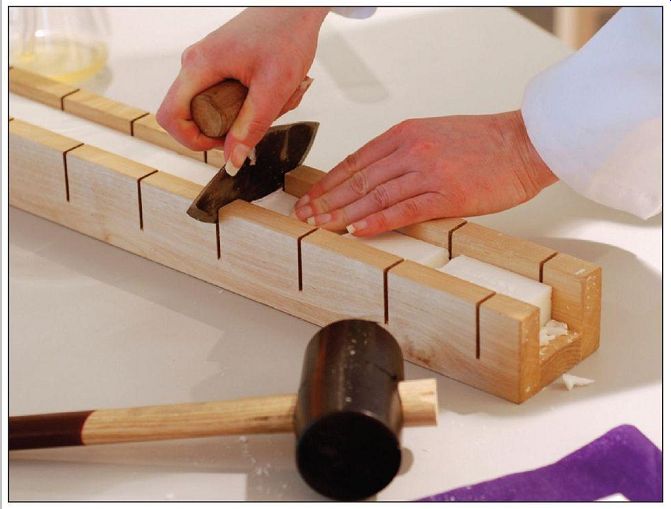

Making soap can be very simple or more involved depending on the desired product. For very evenly shaped and sized bars, a basic mold with slits like this one can be constructed.

---------------

One Substance, Many Varieties

Although, by definition, every soap is made by the saponification (chemical combination) of lye, water, and fat, one soap will differ from the next depending on the kind of fat, the kind of lye, and how much of each is used. Lye made from wood ash, for example, produces soft soap, so called because of its jellylike consistency. In contrast, soap made from commercial lye (sodium hydroxide) will be hard.

Soaps containing coconut oil tend to lather well in cold water but may have a drying action on the skin. Superfatted soaps, such as castile, that contain excess amounts of unsaponified fat are particularly gentle and make excellent toilet soap.

For the sake of convenience or for some special use, soap can be altered in consistency and appearance.

Jellied soap for doing the dishes is obtained by slicing off shavings of hard soap and boiling them in water until they dissolve; about 1 pound of shavings per gallon of water should be used. To produce soap flakes for laundry use, simply grate any ordinary hard soap, then add a few tablespoons of borax to improve water softening ability and quicken sudsing action. The preparation of liquid soap is somewhat more complicated. It is generally based on vegetable oils rather than animal fats and requires the addition of glycerine and alcohol during the soap-making process, followed by filtering. If you want soap that floats, gently whip the warm soap solution with an egg beater just before pouring it into molds; when the soap hardens, the trapped air bubbles will make it float.

The Basics Are the Same No Matter What the Soap

The three ingredients needed to make soap-fat, water, and lye-are all readily available. Lye in the form of sodium hydroxide is sold as dry crystals in many supermarkets and hardware stores, while lye in the form of potash can be made at home from wood ash. Because all types of lye are highly caustic substances that react with plastic, aluminum, and tin, soapmaking utensils should be made of wood, glass, enamel, stainless steel, or ceramic.

Fat for soapmaking can be almost any pure animal or vegetable oil from reclaimed kitchen grease to castor oil.

(See "Rendering and Clarifying" for more information.) The water should be soft. If you are in a hard water area, treat the water with a commercial softener or add a few tablespoons of borax to it. You can also collect rainwater and use it to make soap. The following equipment is needed for soapmaking:

1. A container to hold the lye solution. A 2-quart juice bottle will do. Punch two holes in the cover, one on the opposite side from the other, so you will be able to pour the lye over the fat later on.

2. A 10- to 12-quart pot to hold the fat and lye.

3. A wooden spoon to stir the lye solution and fat.

4. A candy or dairy thermometer that is accurate to within 1°F in the 80°F to 120°F range. For convenience you may want to have two such thermometers.

5. Rubber gloves. Wear these as a precautionary measure, since lye will burn if it touches the skin.

6. Molds for the soap. Prepare the molds by lining them with plastic or greasing them with Vaseline.

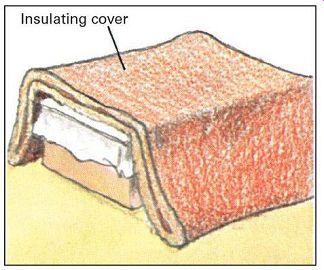

7. Insulation to keep the soap warm after it is poured into the molds. Cardboard, styrofoam, or an ordinary blanket can be used.

8. Enough newspapers to cover work surfaces and floor areas where you will be working.

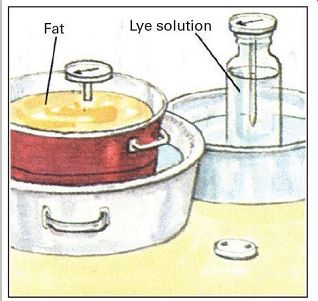

Prepare the lye solution before beginning the soap making process so that it will have a chance to cool. To make the lye solution, pour cold water into an enamelware pot, then add the lye slowly while stirring the solution steadily with a wooden spoon. The reaction between the lye crystals and water will generate temperatures over 200°F.

The container can be placed in a basin of cold water to hasten cooling. Once the solution has cooled, pour it carefully into the 2-quart glass container. If you are going to use animal fat for your soap, you should also prepare it in advance to allow it to cool down (the rendering process takes place at well above the temperatures needed to make soap). Fats can be refrigerated and then brought to soapmaking temperature by warming in a basin of hot water. The type of fat you should use and the relative amounts of fat, lye, and water that should be combined depend on the particular type of soap being made. The standard recipe calls for 6 pounds of beef fat, 2 1/2 pints of water, and 13 ounces of lye crystals. (See p.288 for other recipes).

Saponification is the chemical process by which soap is formed from lye, water, and fat. In order for saponification to take place, the temperature of the lye solution and fat has to be carefully controlled. The simplest method is to bring both the lye and the fat to a temperature of 95°F to 98°F before mixing them together. Some experts recommend that the fat be at a higher temperature than the lye: about 125°F for the fat and 93°F for the lye when beef tallow is used, 83°F and 73°F when lard is used, 105°F and 83°F for half lard, half tallow.

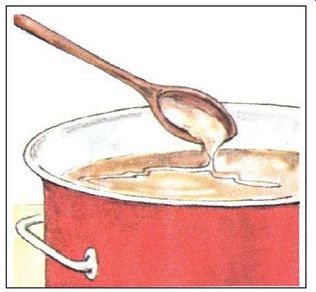

Occasionally, saponification does not take place and the soap mixture separates into a top layer of fat and a bottom layer of lye solution. Generally, the mixture can be reclaimed by heating it to about 140°F while gently stirring with the wooden spoon. Then remove from the heat and keep stirring until the mixture thickens into soap. To test your soap solution, spoon up a bit and let a few drops fall on the surface of the soap; if the surface supports the drops for a moment or two, the soap is ready for the molds.

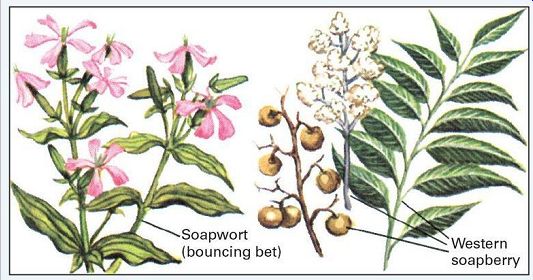

Some plants are natural cleaners

---------

American Indians and early settlers were familiar with a number of plants whose roots, leaves, or berries contain saponin, a natural ingredient that foams and cleans like soap. The best know n and most frequently used of these plants is soapwort, or bouncing bet, a pink-blossomed perennial that grow s wild throughout most of the United states; the juice from the root produces a lather when mixed with water. Another soap plant is the yucca found in Mexico and the southwest. its roots, broken into pieces and mixed with water, form a gentle soap-like compound for the skin and hair. California soap root, a member of the lily family, contains a liquid in the middle of its bulb that makes an excellent antidandruff shampoo; simply crush the bulb center and mix it with water. The fleshy berries of both the southern soapberry tree, found in southern Florida as well as south America, and the western soapberry tree of the American southwest contain seeds that produce lather in water and closely duplicate the cleansing action of soap.

-------------

1. Bring both fat and lye solution to between 95°F and 98°F by placing their containers in basins of hot or cold water, depending on whether they need to be warmed or cooled.

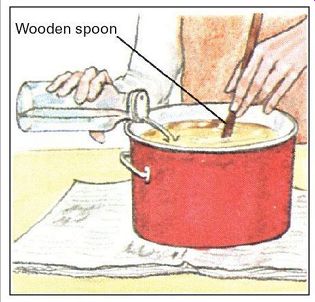

------------- 2. To ensure thorough mixing, stir the fat before the lye is added.

Pour in the lye solution in a steady stream while continuing to stir with an

even, circular motion.

------------- 3. The mixture will turn opaque and brownish, then lighten.

soap is ready when its surface can support a drop of mixture for a moment; consistency should be like sour cream.

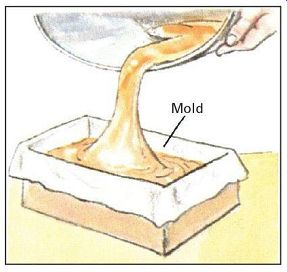

------------- 4. Add colorants, scents, and other special ingredients (adding

them earlier would probably have interfered with saponification). Pour liquid

into molds and place in warm location.

------------ 5. Cover molds with cardboard, styrofoam, or blankets.

soap should be removed from the molds after 24 hours, then left uncovered in freely circulating air for two to four weeks.

Caution: Lye is highly caustic and should be washed off immediately with cold water if it comes in contact with the skin. Avert your face to avoid inhaling the fumes while mixing lye. Always mix lye with cold water, and pour the lye into the water rather than the water into the lye.

From Humble Origins Of Fat and Potash Come Fancy Soaps

Rendering and Clarifying:

Any animal fat and most vegetable oils can be used in soapmaking. A combination of rendered beef fat (tallow) plus pig fat (lard) makes a most satisfactory basic soap and is the mixture most commonly recommended in books, pamphlets, and by manufacturers of lye. Poultry fat alone is too soft but may be used in combination with other fats, and so can most vegetable oils. Coconut oil produces high quality kitchen and toilet soaps, while palm oil soap is gentle and pleasant smelling. Soy bean, cottonseed, corn, and peanut oils all yield low-foaming, medium-quality soap.

The whitest, best-smelling soaps are made from pure rendered fats and oils. However, reclaimed kitchen grease and drippings from the frying pan if properly treated make good soaps.

Rendering is the process of melting and purifying solid fats. Start with twice the weight of fat called for in the soap recipe. Cut the fat into small pieces, and heat over a low flame. Do not let the fat burn or smoke. Although most of the fat will liquefy, solid particles called cracklings will remain. After rendering, strain the liquid into a clean container and refrigerate until it is needed.

Grease and drippings can be reclaimed for soapmaking by clarifying them. Place the fat, an equal amount of water, and 2 tablespoons of salt in a pan and bring to a boil.

Remove from the fire, cool slightly, and add cold water- about 1 quart per gallon of hot liquid. The mixture will separate into three layers: pure fat at the top, fat with granular impurities next, and water at the bottom. Spoon off the pure fat and save it for soapmaking. Even if the unclarified drippings were rancid, they can be rescued by using a mixture of one part vinegar to five parts water in the clarifying process instead of plain water. To deodorize fat, cook sliced-up potatoes in the clarified fat. Use one potato for each 3 pounds of fat. To bleach fat, mix it with a solution of potassium permanganate, a powerful oxidizing and bleaching agent; then warm and stir. Use 1 pint of solution for each pound of fat. To make a pint of solution, dissolve a few crystals of potassium permanganate (available at some hobby supply stores) in a pint of soft water.

Soap as Art:

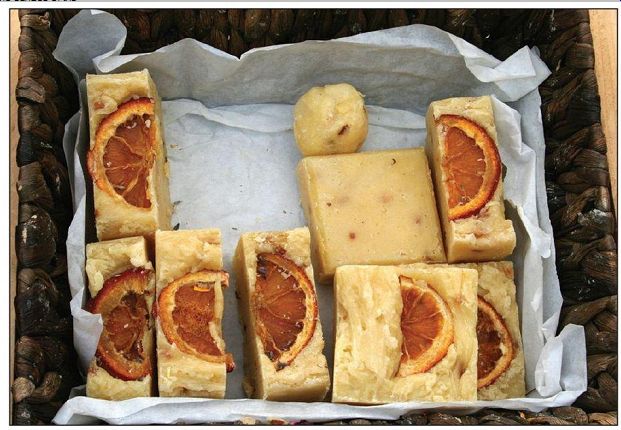

For centuries soap has been a medium of artistic expression. It has been carved, painted, sculpted, packaged, and inlaid with pictures and patterns. Soap decoration begins with the mold. Almost any conveniently sized container can be used; for example, custard cups, cake pans, boxes of all sorts, jello molds, and ashtrays.

Once the soap has set, designs can be pressed or cut into the surface of the individual bars, or the soap can be carved into almost any conceivable shape. The only equipment you need for carving is a small, sharp knife. If the soap is relatively soft, it can be worked like dough. Roll it into balls, or flatten it with a rolling pin, and cut shapes out of it with cookie cutters. An unusual decorative technique is to embed a picture or decal in the top of a bar of soap, then cover the picture with a thin layer of melted paraffin. The paraffin protects the design from water, keeping it intact as the soap wears away around it.

--------- Dried fruit or flowers can be pressed into soap while it's hardening

for a decorative and aromatic touch.

Making Your Own Lye the Old-time Way

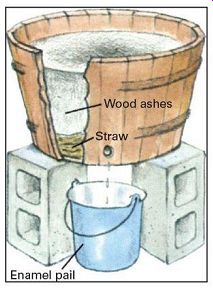

From pioneer times to the present the traditional way to make lye has been to leach it from wood ashes. Lye produced in this manner is known as potash and consists mostly of potassium carbonate, a less caustic substance than commercial lye. Any large wooden container can be used for the lye-making process--the bigger the better, since the more ashes the water seeps through, the more concentrated will be the lye solution. A barrel or large tub with a hole drilled as near to the bottom as possible is excellent for leaching.

Place the barrel on cinder blocks or other supports so that a crock or enamel pot can be placed beneath it to collect the solution as it seeps out. Set up the barrel at an angle, with the opening at the lowest point, so that the lye will run out of it and into the crock. Line the bottom of the barrel with straw to prevent ashes from sifting into the lye solution and pack the barrel with ashes-almost any hardwood will do, but oak, hickory, sugar maple, fruit woods, beech, and ash produce the strongest lye. Finally, scoop out a depression at the top large enough to hold 2 to 3 quarts of water.

To make the lye, fill the depression with rainwater heated to boiling, and let the water seep down through the ashes.

When the water has all seeped away, add more. It will be a while before the lye begins to trickle out the bottom- perhaps as long as several days if the ashes have been packed tightly-but do not try to hurry the process by adding extra water prematurely.

The single bar method

If you want to experiment with a variety of scents, colors, and ingredients, the simplest and most economical way is to prepare a single bar of soap rather than a large batch. You will need the following ingredients:

½ cup cold soft water

2 heaping tbsp. commercial lye

1 cup melted beef tallow

Slowly add the lye to the water, then bring both lye solution and tallow to about body temperature.

Combine the two in a glass bowl and mix slowly and steadily with an egg beater until the consistency is that of sour cream. Pour mixture into mold and age according to standard procedure.

------------ After lye is made test it by cracking in a raw egg. if the

egg barely floats, the lye is good for soapmaking.

Although soap can be made directly from the lye solution, it is often convenient to have the lye in crystalline form, since crystals permit more precision in the soapmaking process. To extract crystalline potash from lye water, boil down the solution in a stainless steel or enamelware pot. At first a dark residue called black salts will form. By maintaining heat, additional impurities can be driven off, leaving the grayish-white potash.

A Survey of Soap Recipes

The standard batch recipe makes an excellent hard soap for laundry and bathing. The recipe calls for one can (13 ounces) of commercial lye, 2 1/2 pints of water, and 6 pounds of fat. About 9 pounds of soap result, enough to make 36 bars of toilet soap. These can be molded separately, or the soap can be poured into a large container, such as a shoebox, and later cut into bars. A combination of half tallow and half lard is usually suggested.

Most other soaps-and there are as many formulas as there are soap-makers--are variations on the standard recipe. A number of attractive recipes are given here, but much of the fun in making soap comes from experimenting with your own combinations of fats, oils, and additives.

Except where noted, the soaps are prepared by the procedure described.

Beauty soaps--Beauty soaps are made by adding scents, oils, and special purpose substances or by replacing some of the water and fat in the standard recipe with new ingredients. The most popular variation is in the amount and type of fat or oil used.

Extra fat or oil makes the soap super-fatted-that is, the soap becomes enriched with excess fat left unaffected by the saponification process. The result is an especially gentle soap suitable for delicate complexions.

Avocado soap. For sensitive skin. Use the recipe for castile soap but substitute 6 oz. of avocado oil for an equal amount of olive oil.

Castile soap. simple but expensive with a hard consistency that is good for carving; named for the kingdom of Castile in north-central Spain where it was first produced.

1 lb. 9 oz. olive oil

3 lb. 10 oz. tallow

10 1/2 oz. lye

2 pt. Water

Coconut and olive soap. Cream colored with rich, gentle lather, even in cold water.

1 lb. 7 oz. olive oil

1 lb. 7 oz. coconut oil

1 lb. 7 oz. tallow

11 1/2 oz. lye

2 pt. Water

Cold cream soap.

Thoroughly mix 2 oz. of commercial cold cream into standard soap just before pouring it into molds.

Lanolin soap. Recommended for dry skin. Add 2 oz. pure liquid anhydrous lanolin to the standard recipe before pouring into molds.

Milk and honey soap. Nourishing for the skin. Thoroughly mix 1 oz. each of powdered milk and honey into any soap while it is still in liquid form, then pour it into molds.

Palm soap. For dry skin. substitute 3 lb. lard, 1 lb. bleached palm oil, and 2 lb. olive oil for the tallow-lard mixture in the standard recipe.

Rose water soap. slightly astringent for oily skin. Substitute 4 oz. of rose water for plain water when mixing the lye.

Scented soaps

Essential oils-powerful aromatic substances extracted from flowers, herbs, and animals-can be obtained from specialty druggists and added in small amounts to your soap before it is poured. Popular fragrances are bayberry, rosemary, jasmine, carnation, and musk. You can also make your own infusions, or strong teas, from various herbs and flowers. steep the plant in boiling water, strain off the solids, and substitute the infusion for some of the water in the recipe. if the infusion is strong enough, you can get the same result by adding it to the soap mixture just before pouring it into molds. However, do not add over-the-counter perfumes or toilet waters: the alcohol they contain will interfere with saponification. Generally, 6 tsp. of scent mixture will be sufficient for the standard batch. Savon au bouquet and cinnamon are among many old-time scent mixtures. You can experiment with other combinations yourself.

Cinnamon. Traditionally, cinnamon soap was colored with yellow ocher. A few drops of oil of lavender can also be added. 6 tsp. oil of cinnamon 1/2 tsp. oil of bergamot 1/2 tsp. oil of sassafras.

Savon au bouquet. in French the name simply means "perfumed soap." A 19th-century recipe for savon au bouquet advises: "The perfume, and with it the title of the soap, can be varied according to the caprice of fashion." 4 1/2 tsp. oil of bergamot 1/4 tsp. oil of clove 1/2 tsp. oil of thyme 1/2 tsp. oil of sassafras 1/2 tsp. oil of neroli

Colored soaps

Roots, bark, leaves, flowers, fruits, and vegetables can be used for colorants. spices such as turmeric and natural dyes such as chlorophyll can be added directly to the soap mixture before pouring into molds. Candle dyes and liquid blueing also work well. Food coloring, however, does not mix well with soap. To obtain your own dyes, make an infusion by pouring boiling water over dyestuff until a deep color is achieved. strain out the solid pieces and use 4 to 10 oz. of the liquid in the standard recipe as a substitute for an equal amount of water when mixing up the lye solution.

Or add the dye just before pouring the soap into the molds. (see natural Dyes, pp.239-243, for more information.) A marbleized effect can be obtained by gently swirling the colorant into the mixture.

Shampoo soap for blonds. Add 3 oz. each of infusions made from camomile, mullein flowers, and marigolds before pouring into molds.

Shampoo soap for brunettes. Add 3 oz. each of infusions made from rosemary, raspberry leaves, and red sage before pouring into molds.

Special purpose soaps

Old-time soap recipes included special formulas for almost every conceivable purpose-insect repellent soaps, antiseptic soaps, medicinal soaps, abrasive soaps, dandruff remover soaps, louse-killing soaps, fungicide soaps. some were useful, many were not, and several were downright dangerous, such as soaps containing mercury chloride for "the itch." Kerosene was a favorite additive but did little except make the soap harsh. Below are two safe and useful recipes.

Grease remover. For use on hands with ground-in dirt and grease. Add 1 oz. of almond meal, oatmeal, or cornmeal to the castile recipe before pouring into molds.

Vegetable soap. For strict vegetarians; reddish in color, soft enough to mold into balls. Vegetable soap is extremely mild and gentle. it can also be used as a base for a dry hair shampoo soap. simply add a mixture of 1 1/2 oz. glycerine and 1 1/2 oz. castor oil to the liquid soap just before pouring it into molds.

2 lb. 10 oz. olive oil

1 lb. 7 oz. of solid-type vegetable

2 pt. water

1 lb. coconut oil

10 1/4 oz. lye shortening

Sources and resources

Books:

Bacon, Richard M. The Forgotten Arts. Book 1. Dublin, N.H.: Yankee, Inc., 1975.

Bramson, Ann. Soap: Making It, Enjoying It. New York: Workman Publishing, 1975.

Cavitch, Susan M. The Natural Soap Book: Making Herbal and Vegetable-Based Soaps. Pownal, Vt.: Storey Communications, 1995.

Seymour, John. The Forgotten Crafts. New York: Knopf, 1984.

White, Elaine C. Soap Recipes: Seventy Tried and True Ways to Make Modern Soap with Herbs, Beeswax and Vegetable Oils. Starkville, Miss.: Valley Hills Press, 1995.

===