Landscaping for energy conservation is not a new idea. Before the age of cheap heating fuels, it was common knowledge that a shelter should be built to take advantage of prevailing winds, the angle of the sun, and topographical features such as hills, lakes, and stands of trees. Before the invention of air conditioning and electric fans, large trees were often planted around houses to provide cooling shade in summer. When the only heat a family had in winter came from the wood they cut, wind breaks were used as an important method of conserving heat.

During the few short decades between the development of more advanced energy sources and their rising costs today, little thought was given to most of the once-commonplace energy- saving considerations. But now that energy conservation is again important, we can learn from the past and adapt that knowledge to our current needs.

• Microclimates: If you’ve ever climbed or walked around in the mountains at 10 or 12 thousand feet on a blazing hot summer afternoon, you may have noticed a few small patches of snow nestled into north-facing crevices of thick granite walls. These cold, white anomalies exist in tiny microclimates that are related to, but quite distinct from, the larger climate that surrounds them.

The same kinds of climatic discrepancies exist around your own house, although probably to a more moderate degree.

Your geographic region has a climate you might describe as “cool,” temperate,"hot and dry," or "hot and humid." Within that regional climate are numerous local climates; in a hot, dry region, a stream may run on a green valley floor that gets little sun and is really rather cool and moist. and the local climate itself may be made up of multiple microclimates. You can take advantage of your regional, local, and microclimates to save energy in all sorts of ways that will also make your house more comfortable and attractive. In assessing your needs and applying your solutions, bear in mind that in some ways your particular microclimate may differ even from that of your next-door neighbor. Always look at your own situation closely.

• Working with your landscape: De pending on your location, the natural landscape may help to conserve energy. Plants at ground level evaporate moisture, cooling the air all summer. A small body of water, set between the southerly wind and the house, will provide natural air conditioning in warm weather.

There are also structural changes you can make to your house that can be a very effective means of cutting energy bills. Awnings and overhangs are two valuable additions.

When you’re looking for ways to con serve energy and cut down on heating and cooling bills, it’s worth considering all aspects of your property. There may be unexpected savings that only a landscaping project could offer.

• Windbreaks: While wind directions vary, they are fairly predictable within any general region. In most parts of the United States, except along the coasts, cold winds rush down from the north in winter and soft breezes waft in from the south in summer. From the viewpoints of both comfort and conservation, it makes sense to encourage the soft breezes and discourage the cold winds.

A windbreak is any sort of barrier that stops the wind. It can be set up on the north side of your house and , de pending on the intensity of the winds, it may reduce your winter heating load as much as 20 to 30 percent. A wind break should be constructed to allow some wind to pass through it; otherwise, the uneven speeds of passing winds may create eddy currents, which in turn may create unexpected winds on the far side of the house.

Windbreaks can be constructed of masonry or wood, but the most effective ones are natural: trees, tall shrubs, even networks of vines. The greenery not only acts as a block and drag on the wind, but it also gives moisture to the air that reaches the house, which raises the comfort level for the residents in cold weather. A thick screen of vegetation can also absorb some noise, which could be another consideration if you live in a city or near a highway.

Should you consider planting or building a windbreak? There’s no universal answer; but if you have already weatherized your house as completely as possible with caulking, stripping, insulation, storm windows, and so on, and if nevertheless there’s enough infiltration to wiggle a sheet of cellophane hung by a window on a wire hanger, the answer probably is yes. On the other hand, you may want a windbreak long before you know the effectiveness of your other weatherization measures.

Unfortunately, you can’t measure the quantity or quality of wind in order to determine whether or not to have a windbreak. There is no R-value for wind breaks, and deciding to plant or build one is largely a subjective matter.

Landscaping for Conservation

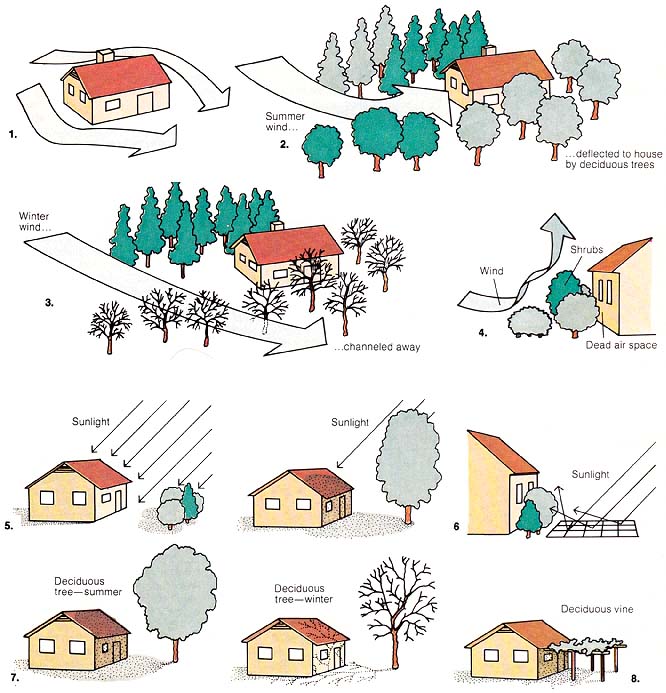

1. Once you understand the pattern of air movement around your house.

.

2. you can use trees and other landscaping features to direct warm summer breezes into the house. (deflected to house by deciduous trees)

3. While channeling cold winter winds away from it.

4. Closely planted, dense-growing shrubbery can be used to block wind at the same time it provides an insulating dead-air space next to the house.

5. In general, low plantings admit the sun, while tall ones block it out.

6 But low plantings can be used to block reflected sunlight.

7. Tall deciduous trees, planted on the south side of your house, will block the sunlight during the hot summer months, and admit it during the cold winter months. Similar plantings on the west side of your house will help to block afternoon sun in summer as well.

8. Deciduous arbors and trellises can have much the same effect.

If you do put up some sort of wind break, the most logical location is between your house and the direction from which the prevailing cold winds blow. As to size, there is a traditional rule of thumb: choose a tree that will reach 1½ times the height of your house at maturity, and plant it at a distance equal ling about five times the height of your house. (Of course, if you are building your windbreak rather than planting it, you needn’t wait for it to grow to the right height.) But this rule of thumb is only an approximation. If you live on the windy side of a hill, your windbreak may have to be higher or closer than tradition dictates. A broad exposure to a wide field of wind may require a longer break than a narrow exposure will. and the limits of your property line or other encumbrances may prohibit you from following the ideal guidelines.

The same problems that apply to any subjective matter also bedevil the question of windbreaks. You must assess your own situation; modify that assessment according to your own personal needs, desires, and abilities; and choose the likeliest solution. Our guidelines should help you arrive at the best compromise possible.

• Trees: There are basically two kinds of trees: evergreen and deciduous. Because evergreens retain their foliage all year, they are particularly useful on the north side of a house, where they can provide the greatest shelter when the cold winds blow. On the other hand, because deciduous trees lose their leaves in the fall, they are excellent protection for the west, east, and south sides of a house. Their broad foliage helps reduce the heat all summer, and then lets the sunshine through in winter, when the leaves are gone. Deciduous shade trees have been shown to make a difference of 20°F to 40°F, in the attic temperatures on a warm, sunny day. Small trees can reduce reflected heat from pavement near the house, reducing indoor temperatures in the summer.

Trees used expressly as windbreaks should be positioned as noted above and should be capable of maturing to the proper height for maximum effectiveness. The number of trees and the distance between them will depend on the breadth of their root systems and the eventual span of their branches.

As you might imagine, where one tree breaks a little wind, a stand of trees can break substantially more. If you’ve ever flown over the Great Plains on a clear day, you’ve looked down on vast farms whose building complexes are tucked off in a corner by themselves, protected by several rows of trees that have been planted to form a wedge that faces into the prevailing winds. The farmhouse itself is nearly always in a pocket of this wedge, and shaded on the south by tall deciduous trees.

• Shrubs: Tall shrubs, planted densely and close to the house, offer a layer of natural protection that cuts down the wind’s impact on the building. An experiment in South Dakota compared two homes: one with a shrub windbreak, and one without. The home protected by shrubs consumed 25% less energy. Shrubs also provide an insulating dead- air space. Here, the dead-air space works on the same principle as it does in a storm window: since static air transfers heat poorly, the space where the air is trapped (in this case, between the foliage and the siding) becomes insulation. For this reason, shrubs are preferred over trees for plantings near the house because of their more compact nature. Shrubs can also reduce heat reflected from pavement near the house.

• Vines: Vines can help cool your house in summer and warm it in winter. A variety of vines can be trained to trellises immediately beside the house, or grown to climb a bare south or west wall to shield it from summer sun. Evergreen vines can be grown in the same way on a north wall to provide some winter insulation. A lathe shade structure covered with a deciduous vine can be particularly effective on the south. You can create a green overhang, an awning or a ceiling over a patio. Each will re duce both direct and reflected heat, performing much the same function as a deciduous tree. Our Guide to Garden Construction Know-How contains detailed instructions for building such shade structures.

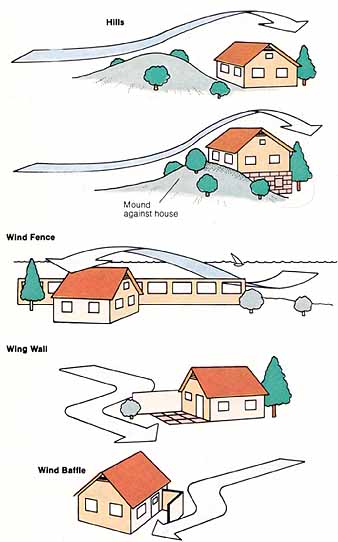

• Hills: Hills, whether natural or man made, can offer protection against the cold. A man-made hill—a berm—works effectively and immediately. A berm can direct the movement of cold air around the house, encouraging it to run off down a slope instead of catching next to the foundation like a pool of water. If the berm is high enough, it can even deflect the wind over the house.

Perhaps its most effective use is as insulation. Consider mounding soil up against your house to take advantage of its natural insulative qualities, but only if your home has the appropriate masonry structure to accommodate the constant moisture sitting against it. Because a berm can be planted, it can blend attractively with your other surroundings.

• Structures: Air flows much as liquids do. and , as with liquids, there is more than one way to control the flow and direction of air.

So far we have been discussing wind-breaks. A wind-break may be likened to a breakwater pier that protrudes out from shore into a large body of water such as an ocean or a large lake, and whose purpose is to break up and dissipate the force of strong waves, especially during storms.

A wind fence is a different matter, and may be likened to a seawall, which does not break up the force of strong waves, but rather receives their impact directly, absorbing it and protecting the land and structures that lie behind it.

Whereas a windbreak lessens the force of wind for a defined area, a wind fence is intended to create a completely calm space immediately behind it. A wind fence may be as simple as a piece of canvas strung up in the face of the wind, or as determined as a brick wall. The former should have small holes in it to allow some wind to pass through, or it will be torn down in a strong wind; the latter should be strong enough to withstand far greater impact. A wind fence can be effective if, for instance, you have strong winds gusting over your patio and into your back door. It can make both outdoor and indoor living more comfortable.

A wing wall is an effective way to divert most winds from around part of your house, and may create a kind of sheltered patio on which, as you sit and sip your morning coffee, your newspaper will barely be ruffled, even though nearby tree branches may sway and dead leaves may leap like lizards across the open spaces of your yard. To be most useful, the wall should be adjacent to an outside door, and should block winds from the north and west of your house. (In general, these are the ones that blow both hardest and coldest.)

Again, if you have a particularly windy area near an entrance to your house, a wing wall can be very effective in reducing infiltration as well as making the outdoor living space more comfortable. A wind baffle can increase your cold-weather comfort, particularly if you live in a climate where winter rubs the discomfort in with chill winds that whip through your parlor every time you open the door. Essentially, a baffle stands mid-way between a windbreak and a wind fence.

It is a mini wing-wall that extends from your door frame and blocks the direction of your strongest winter winds. Some baffles may extend several feet out from the door frame, then attach to another baffle at 90-deg, blocking the wind still further. Only you can decide how extensive your baffle should be.

Wind current patterns and how to control them: Hills; Wind Fence;

Wing Wall; Wind Baffle

Next: What to Look For in Buying a House

Prev: How to Insulate